Launch AI-stronauts into Space

Robots with personalities could reignite our fascination with the cosmos

It’s easy to love an astronaut—and easier still to hate an AI.

What’s more heroic, more professional, more emblematic of human ingenuity than Neil Armstrong stepping onto the lunar surface?

I’ve watched every Apollo documentary and absorbed all the great myths and parables of space sci-fi. I believe that space exploration is humanity’s ultimate mandate: the quest of quests. Astronauts are like secular saints to me.

AI, by contrast, is a tougher sell.

What’s more dispiriting than a clumsy chatbot? Soulless, derivative, sycophantic jabberers. “AI characters,” “friends,” and “personas”—the most ambitious experiments have been half-baked at best, and at worst accompanied by headlines about adolescent psychosis and teenage despair. After a few years of breathless enthusiasm over large language models, the pendulum (rightly or wrongly) is swinging back toward pessimism.

But our devotion to human heroes—and our suspicion of artificial ones—will need to change if we’re to explore the stars. As I touched on in Quest 12: Send the Robots First, the cold economics and harsh realities of outer space demand we embrace autonomous machines.

Unfortunately, we have a public-interest problem when it comes to space exploration: few people know or care about what NASA is doing. Why should they? Space, for all its wonders, is mostly big, empty, and boring. Try watching the livestream from the International Space Station for more than a few minutes.

Meanwhile, here on Earth, we’re in the midst of an attention war, an informational assault on our senses—not by a single antagonist, but by the invisible hand of market incentives and sleek distribution systems that fit in our pockets. We’re being corralled toward our basest desires without any moral framework for deciding what’s worth our time. Instead of pursuing Star Trek visions, we’re lost in Cracker Barrel debates and cycles of outrage.

For people to care about space exploration, there have to be people—human stories, human drama. This is our nature. But space resists us at every turn: incomprehensible distances, crushing gravity, unlivable cold, lethal radiation, an existential void so terrifying that even Captain Kirk himself was shaken by it.

It’s a thorny dilemma. What’s often overlooked is that the problem of space exploration—the costs, the risks, the lack of progress—is also an attention problem. The two are intertwined.

So how do we push the ball down the field and to the stars without (1) risking human lives at great expense and (2) losing fickle human interest?

How do we put interesting characters (and, with them, our attention) in places where people can’t go anytime soon?

Enter the good robots. Let them pave the way to the Moon, Mars, and beyond—cheaper, safer, and far more resilient than any human crew. But machines alone won’t hold public attention. For that, we’ll need to give these robots personalities, stories, and voices.

R2-D2, WALL-E, Data, and other friendly AIs are fictional darlings; AI astronauts could be their real-world successors, narrating missions and enlivening space exploration in a crowded attention economy.

This week’s quest is go for launch. First checkpoint: why, oh why, can’t we just send humans?

The End of Astronauts

This question is at the heart of The End of Astronauts: Why Robots are the Future of Exploration by astrophysicists Donald Goldsmith and Martin Rees. Their book turns conventional thinking upside down, claiming that human spaceflight—once celebrated as the pinnacle of exploration—is becoming obsolete. Robots, they argue, are rapidly overtaking humans in capability, safety, and (most importantly) cost-efficiency.

The cost disparity between human and robotic missions is stark. Some estimate that manned spaceflight costs more than 100x as much as comparable robotic missions when all life support and safety systems are tallied. The Mars rovers missions cost a few billion dollars a pop; according to a 2019 analysis by the Institute for Defense Analyses (IDA), “a mission for astronauts to orbit the planet without landing on it would cost $117 billion through 2037.”

Astronauts are, pardon the pun, astronomically expensive. “We cost far more than robots to maintain, and we expect to return home,” write Goldsmith and Rees. Human missions require complex redundancies: oxygen, food, water, radiation shielding, medical and psychological support, fuel for the return trip. Each kilo, each maintenance system, adds exponential cost.

Robotic craft, in contrast, can be rugged, odd-shaped, and expendable. They can linger in dangerous places, function without life support, and push farther with fewer constraints. “Boots on the ground” were once necessary for mission success, but that’s no longer the case. It may be, as Goldsmith and Rees suggest, that our attachment to human astronauts is more sentimental than practical.

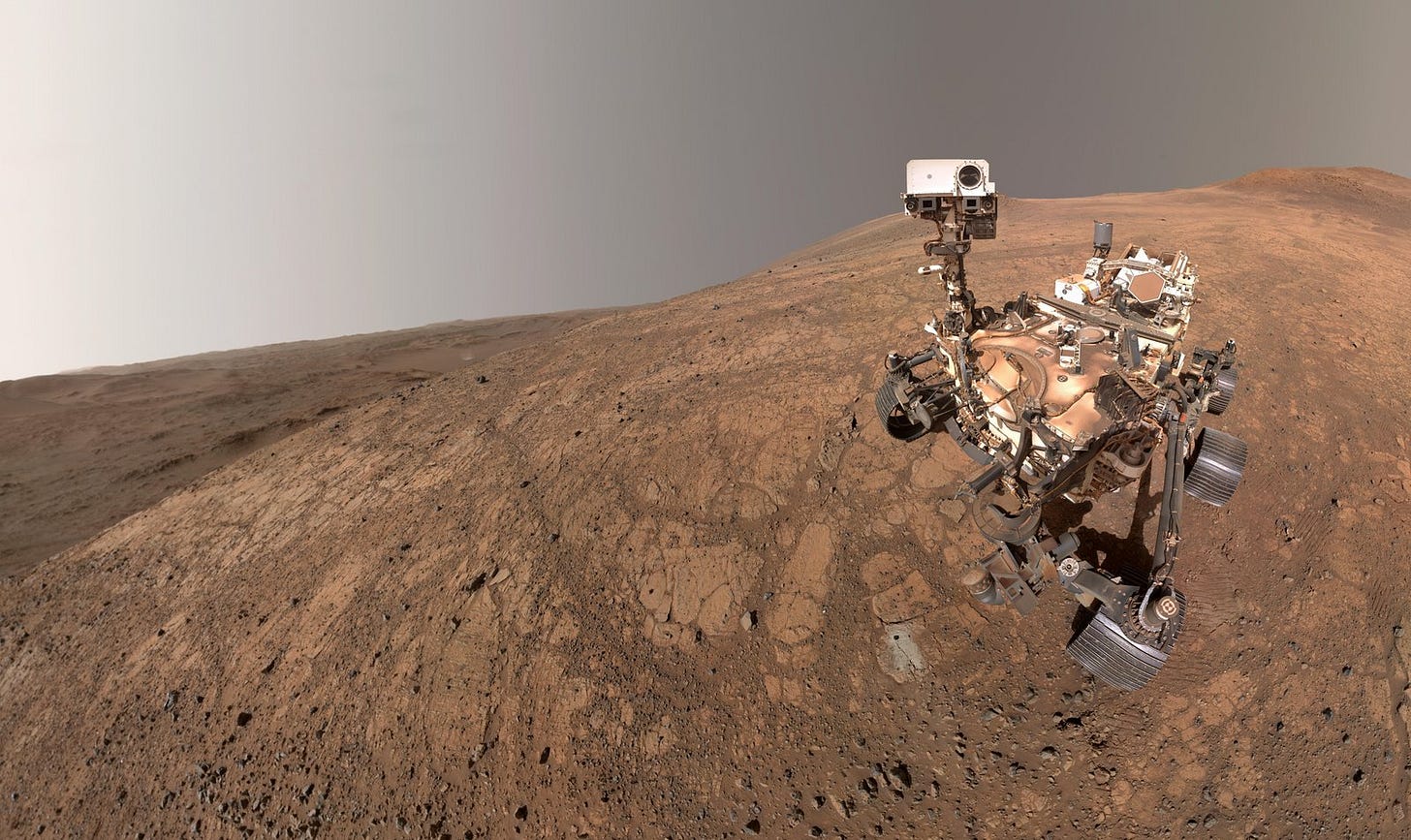

This week, NASA made headlines by publishing groundbreaking results on the search for biosignatures in Martian rocks, sharing data and a selfie from the Perseverance rover.

They found “compelling chemical signatures in the data,” combinations of compounds that are difficult to explain absent organic processes. Not quite a smoking gun for life on Mars, but close.

“This finding [...] is the closest we’ve come to discovering ancient life on Mars,” said Sean Duffy, NASA’s acting administrator. At the press conference, Duffy and a panel of scientists carefully laid out their findings: every claim was hedged, every conclusion provisional. It was good science on display— incremental and precise.

But c’mon!! I wanted more. Not more data, but more story, more excitement.

I kept coming back to the selfie Perseverance had sent from the Martian surface—a squat rover against the red-grey horizon, oddly endearing with its lone eye.

Shouldn’t we hear the news from...her? In the age of rapidly improving AI, is that really such a stretch?

Send the “AI-stronauts”

Obviously, there’s an ongoing debate about how far AI can go.

Some experts, including (conveniently enough) the CEOs of AI companies like xAI’s Elon Musk, OpenAI’s Sam Altman, and Anthropic’s Dario Amodei, suggest that we are just a couple of years away from artificial general intelligence—a system capable of reasoning as flexibly as a human. That’s almost certainly optimistic.

But most researchers agree that within five years we’ll have AI agents and AI characters (customized chatbots) that feel more convincing than today’s iterations. Increasingly, they will be able to hold seamless conversations, handle natural interruptions, carry memories across interactions, and generate responses that are indistinguishable from those of a human being.

We’re getting close. Researchers at MIT, Stanford, and elsewhere are experimenting with “embodied LLMs”—language models paired with robots that can perceive and act in the world. They are making progress toward “scalable, efficient and ‘intelligent robots’ able to complete complex tasks in uncertain environments.” Like, say, an asteroid or a planet.

I’m not proposing that a Mars rover will become C-3PO overnight. These systems won’t be conscious, but they don’t have to be. Even with the inevitable lag in signals between Earth and Mars, a rover given the illusion of personality—curious, cautious, maybe even a little irreverent—would be far more engaging than today’s silent machines.

Platforms like Character.ai, Replika, ElevenLabs, and HeyGen already generate interactive personalities with faces and voices. It’s not hard to imagine NASA or SpaceX putting these technologies into a rover—or simply overlaying a rover feed with an avatar—so that suddenly you don’t just have a hunk of machinery but a “living,” speaking character.

Space robots that crack jokes, interact with Mission Control, and narrate their adventures could give our explorations the narrative and viral lift that’s so sorely needed. When SpaceX launched Elon Musk’s Tesla Roadster into orbit in 2018, the video feed of “Starman” drifting through space drew tens of millions of views. It was more spectacle than science, and that’s okay.

It’s also okay if the early innings of AI-stronauts are mostly smoke and mirrors. NASA already anthropomorphizes its rovers in press releases and social media posts. The difference is that with modern AI and improvements in communication, those voices could be close to real-time and interactive. Kids could submit questions to the rover and get answers back in its “voice.” Journalists could conduct interviews with a crew of robots in orbit or on the Moon. Fans could follow along on TikTok as AI-stronauts narrate each stage of the mission. Missions could have multiple personalities—a cautious scientist, a wisecracking engineer—who could debate findings in public view.

The bottom line is this: we need to push our collective human consciousness out of filter bubbles and into outer space—even if, at first, our representatives are neither human nor conscious! The point is that we’re embedding narrative structures (characters, plot lines) in places where hitherto story has been largely unable to go.

Today’s children will grow up in a world where AI “friends” are not unusual. That is a sobering reality—and no one wants a HAL 9000 in orbit—but it’s also an opportunity. We should deploy this technology in a conscientious way toward noble causes. Space exploration fits the bill.

Voice and character models already run on consumer devices. The marginal cost of embedding them in a rover feed or orbital satellite is trivial compared to the billions spent on launch hardware. What’s missing is the will to treat public engagement as central, rather than peripheral, to exploration.

If the future of space is robotic, then AI-stronauts—oddly enough—may be our best chance to keep the story human and the public engaged.

With that—

Here’s Quest 31:

Launch AI-stronauts into Space

Key Details:

Prototype your own AI-stronaut: use a free tool like Character.ai or ChatGPT voice mode to create a “space explorer” persona. Give it a name, a backstory, and share a short dialogue or clip.

Follow and amplify real missions: tune into feeds from NASA and SpaceX. Join conversations, and push for AI + robotics as a narrative bridge to human exploration and (eventually) colonization.

Pitch AI-astronauts: write a short note or tweet to NASA, SpaceX, or other space-focused organizations explaining why missions should include AI characters. Public pressure and visibility will help shape what agencies try next.

As always, thanks for reading!