Send The Robots First

How AI, automation, and a certain form of faith will pave the way for Mars colonization

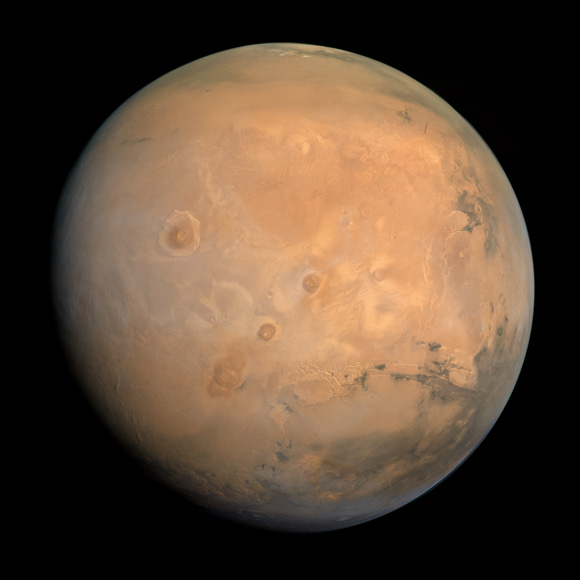

Mars as captured by the Hope orbiter

Greetings, adventurer!

First, a trigger warning: Elon Musk will feature prominently in this post. No doubt, the world’s richest man is radioactive right now, a walking lightning rod.

For some, he’s beyond redemption, deserving only outright and unequivocal condemnation. For others, Musk is a once-in-a-generation visionary, a real-life Tony Stark who will stop at nothing to remake the world in his own incendiary image.

Here, I’m focused on Mars. Like it or not, that means reckoning with Elon and his juggernaut companies, including SpaceX, Tesla, and xAI. Whatever your stance on Musk, he has altered—and will continue to alter—the trajectory of the 21st century and beyond.

That’s not hyperbole. We’ll get into why momentarily. But first—why Mars?

Why Go to Mars

To approach this question, we have to think in decades and centuries, not months or years. We also have to foreground planetary risks—asteroid impacts, nuclear war, runaway AI, climate catastrophe—and the ever-present possibility of an extinction level event.

Making the human race a multiplanetary species is the ultimate hedge against disaster. Full stop. And Mars is the only place in our solar system even remotely habitable with current or near-future technology.

Robert Zubrin, one of the foremost Mars advocates, lays it out clearly in The New World on Mars:

In contrast to Earth’s desert Moon, Mars possesses oceans of water in the form of huge glaciers and ice sheets, and it’s frozen into the soil as permafrost. It also holds vast quantities of carbon, nitrogen, hydrogen, and oxygen, all in forms readily accessible to those clever enough to use them. Additionally, Mars has experienced the same sorts of volcanic and hydrologic processes that produced a multitude of mineral ores on Earth. Virtually every element of significant interest to industry is known to exist on the Red Planet. With its twenty-four-hour, day-night cycle and an atmosphere thick enough to shield its surface against solar flares, Mars is the only extraterrestrial planet that will readily allow large-scale greenhouses lit by natural sunlight. For our generation and those to follow, Mars is the New World.

So, in summary, there are two fairly obvious reasons we should go to Mars: (1) to increase humanity’s odds of long-term survival and (2) to unlock new economic opportunities.

But there’s a third reason—admittedly a little fuzzier—that I want to touch on at greater length. It is, for lack of a better term, quasi-religious.

Existence itself is the grandest mystery of all. Why is there something rather than nothing? Or, as Jim Holt put it in his excellently written and titled book, Why Does the World Exist?

Unless you’re a religious dogmatist or an ardent sort of atheist-materialist, then the answer, for now, is that we simply don’t know. My personal belief is that the ultimate riddle of everything somehow involves human beings and our inner/outer explorations into teleological understanding. This is wildly anthropocentric, I know, but even still I can’t escape the gnawing sense that we are meant to explore outer space.

I touched on this in a 2018 article for the Millions:

From our earthbound perspective we refer to all of this cosmic immensity with a modestly geocentric name: ‘outer space.’ To me, this seems like a compartmentalization of epic proportions. On the one hand, there is the world as we know it, the ground-level of human life and everything it entails: the whole arc of history, the transformation of our natural environment, nervous first dates over coffee. On the other hand, there is the remaining 99.999 percent of material reality that exists beyond the stratosphere, always there but rarely acknowledged.

To go to Mars is to take the next step in a fundamentally cosmological journey into the remaining “99.999~ percent of material reality”: addressing our deepest metaphysical yearnings by venturing “out there.” This amounts to a statement of faith in science and technology as a form of deliverance—not tech at its worst (addictive, ad-riddled, stultifying), but at its best (problem-solving, enlivening, expansionary).

Webb’s First Deep Field image

If you subscribe to this form of faith (as I do), it negates the commonly held notion that we can’t set out for the solar system and the stars until our own planetary house is in order. According to this view, humanity has no business leaving Earth until poverty is eradicated, CO2 levels are stabilized, and the worst excesses of capitalism are curbed.

But I think this is backwards. Until we decide to peacefully pursue the mystery box of existence itself, we’ll remain mired in culture wars, literal wars, and all the inner wars of self-doubt and self-sabotage. We are losing the plot if we lose sight of the cosmos. To cite another cliché, “the perfect is the enemy of the good.” Things on Earth will never be perfect.

On a more practical note, remember too that NASA spin-off technologies have reshaped our planet for the better. GPS, water purification systems, improved prosthetics, medical imaging, the memory foam in your mattress: the push for offworld exploration has already enhanced our lives here at home.

My religious/political views summed up in a single image

Now here’s the rub: to fulfill what I see as our human destiny, we’ll have to depend on technology and technologists—including, for now, some of our most dubious tech and our most egotistical technologists.

The Robot Pioneers

Have you ever seen The Martian?

It’s a great movie—based on a pretty good book. A classic man-versus-nature plot. Matt Damon gets his ass kicked for two hours and “sciences the shit out of” surviving alone on Mars for 564 days. The film was lauded for its scientific accuracy, particularly its treatment of astrobotany.

But I’d argue it’s unrealistic on one point: those astronauts would not have been there without autonomous robots having better laid the groundwork for their survival. To understand why, you have to appreciate just how unbelievably hostile Mars is.

It’s not just the cold (average temperature: -85°F) or the lack of oxygen (breathe in and die). It’s dust storms, cosmic radiation, and weak gravity slowly sapping your bones and muscles. Every single second on Mars is a fight against an environment in which no living thing (as far as we know) evolved to live.

This is why AI-driven robots—ones that don’t need air, don’t get cancer from radiation, and don’t care if they’re trapped in a sandstorm—should be the first true Martians. Before humans ever step foot on the planet for anything more than a photo op, fleets of autonomous machines will have to build the infrastructure: habitats, power grids, resource extraction sites, water filtration systems, perhaps underground tunnels to shield against radiation.

This is the ultimate endgame of the AI wars: a much more advanced ChatGPT, DeepSeek, or Elon’s own xAI plugged into a robotic humanoid with the prime directive of settling planets for us. It’s also why we shouldn’t necessarily kick ourselves that we haven’t gone back to the Moon sooner or pulled off a manned Mars mission faster. Consciously or not, we’ve been waiting on AI to catch up with our progress in rocketry. Everything becomes easier with smart robots.

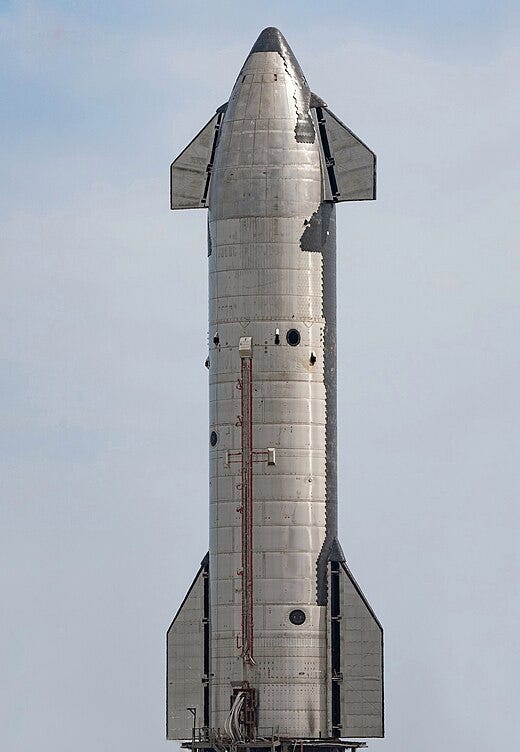

Getting to Mars isn’t really the problem. As Zubrin writes, “The question of colonizing Mars is not fundamentally one of transportation. If we were to use a vehicle comparable to the SpaceX Starship now under development to send settlers to Mars on one-way trips, firing them off at the same rate SpaceX is currently launching its Falcon rockets, we could populate Mars at a rate comparable to the rate at which the British colonized North America in the 1600s—and at much less expense relative to our resources.”

I disagree with Zubrin on one thing: we shouldn’t send humans to the Red Planet before the groundwork is laid by autonomous robots. Did you catch his subtle reference to “one-way trips?” “A bunch of people will probably die” colonizing Mars, according to Musk. Why throw a million people into a brutal fight for survival when robots could first make Mars a little more livable and a return journey more likely?

Starship prototype SN20

Starship, despite recent setbacks, plans to send uncrewed Starships to Mars in two years. Because of Musk’s ridiculous antics, it’s actually been underreported—underemphasized—just how impressive SpaceX’s achievements have been. The progress they’ve made in reusable rocket technology, rapid iteration, and launch cadence is remarkable.

Musk famously likes to invert the old adage “where there’s a will, there’s a way” into “where there’s a way, there’s a will.” He’s right about this. Often, our intentions follow our actions, not the other way around. It’s counterintuitive, but history bears it out: technological capability breeds ambition. You didn’t want to doom scroll before you had a smartphone.

This mindset underpins Musk’s lifelong obsession with Mars and the companies he’s founded, each contributing its own “way” to his multiplanetary will: the Boring Company (tunneling tech), Neuralink (human adaptability), Tesla (transport, robotics), xAI (artificial intelligence), and, of course, SpaceX (spaceflight).

Despite his 2023 call to pause AI development—while, laughably, he was working on his own AI company—Musk is essentially a Milton Friedman-style accelerationist who sees the human species (and, I suspect, his own mortal self) in a race against time.

There’s a cold logic to it all. To survive long-term, humans must become multiplanetary. Anything slowing that down is a waste of time. And given the hostility of Mars and the vast distances between planetary systems, robots must go first.

None of this defends what Musk is doing in the short term. But it’s a different lens through which to view it. His worldview is not idealistic in the way we often think of visionaries. It’s brutally pragmatic, with an almost amoral fixation on momentum. The ends justify the means, and the means create the ends.

This is where faith becomes dogma. At what cost should we pursue the stars and their mysteries?

What’s Next?

If we do decide to go for it, to send the robots first, then there’s just one thing: we, uh, need the robots.

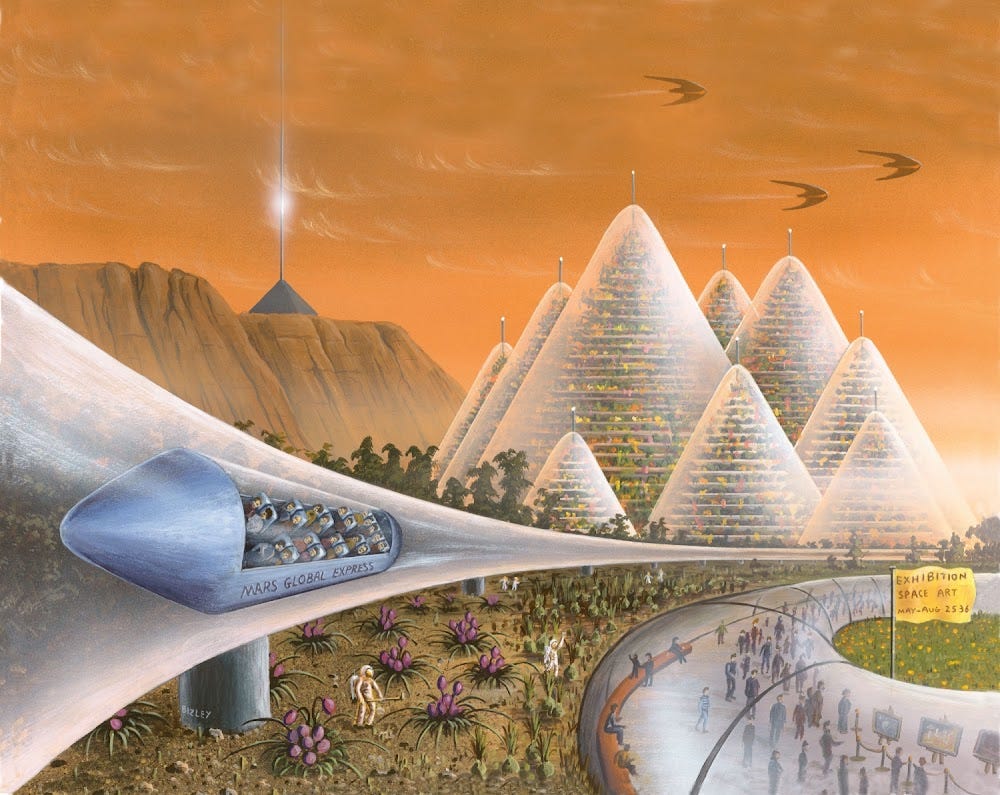

We’ve explored here a circuitous but logical moral claim for why AI development should extend beyond boosting white-collar productivity or helping college kids churn out essays. The real stakes are planetary. The coordination of many technologies in development—autonomous navigation, robotic construction, self-repairing systems, and AI-driven resource extraction—will allow robots to settle Mars before us, building the infrastructure necessary for human survival.

So, how far off are we?

If you ask Elon, not very. He envisions Optimus bots on Mars within the decade. Given his track record for prediction, this timeline is wildly optimistic.

The Optimus

The reviews on Optimus have been mixed. Some roboticists criticize it as basically a sleek looking clone of the Honda Asimo; others are excited about Optimus’ movement and object-manipulation capabilities.

NASA is designing Valkyrie, a humanoid robot designed for deep-space missions, particularly tasks requiring dexterity. But honestly, as far as humanoid robots go, it’s more likely that the first Martian workers will look nothing like us. Boston Dynamics' robotic quadrupeds—like Spot, already deployed in hazardous environments on Earth—are better suited for scouting unstable terrain and navigating the unpredictable Martian landscape.

Tales From A Robotic World

Some researchers are exploring more adaptive, biologically inspired robotics. As reported by Dario Floreano and Nicola Nosengo in Tales From A Robotic World, Barbara Mazzolai, an Italian biologist-turned-engineer, has spent years developing plant-inspired robots capable of burrowing into soil, anchoring themselves, and even growing infrastructure. In theory, swarms of these “plantoid” robots could analyze Martian soil, search for water, and even release chemicals to make it more hospitable for future colonists. Meanwhile, her climbing "growbots" could form stable networks by attaching to existing structures, autonomously building everything from power grids to underground habitats.

Still, this is all moot until we hit artificial general intelligence (AGI) and these robots can actually learn—what Yann LeCun calls developing a "world model." Right now, most robotics rely on narrow AI, which is great for specific, repetitive tasks but useless when confronted with something unexpected. A truly autonomous Martian workforce will need machines that can adapt in real time without constant human oversight—the distance between Mars and Earth is simply too far for regular communication.

LeCun, a pioneer in deep learning and Chief AI Scientist at Meta, argues that for AI to function truly independently, it must build an internal representation of reality, allowing it to simulate future outcomes and plan accordingly. Without this, robots will remain glorified Roombas, impressive in controlled environments but hopelessly lost in the chaos of an alien world.

This, then, is what’s required to become multiplanetary: putting a Ghost into the Machine, giving AI intuition and autonomy to act. And that’s scary.

To achieve this:

City on Mars in a Far Future, Richard Bizley

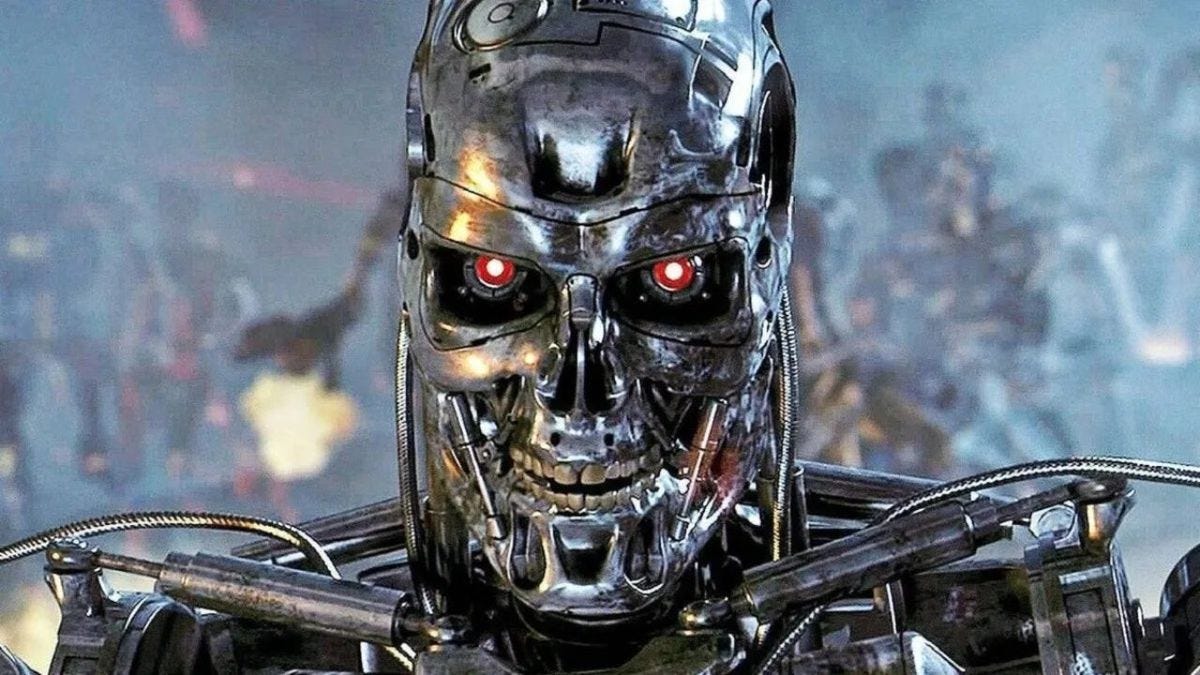

We risk this:

The T-800 from Terminator

The stakes are high. You have to ask yourself: what’s our human destiny?

We descend the Tower with our heads spinning and lots to think about. The world looks a little different now. If we’re going to reach for the cosmos, we have to decide: who goes first?

You know what I think; share your thoughts in the comments below.

Here’s Quest 12:

Send the Robots First

Key Details

This quest is admittedly a little grandiose, but the groundwork for humans on Mars is being laid right now. So, here’s the challenge: engage with this future in a tangible way.

Track the missions – Follow Starship’s progress; keep tabs on NASA’s Valkyrie and Artemis programs; watch what’s happening in robotics labs like Boston Dynamics or AI research at DeepMind and xAI. Plug into this space a little more, and do your part to shape the conversation.

Support the builders – Support open-source AI, follow space-related legislation, or fund innovative projects via platforms like Kickstarter and Patreon. If you can’t stomach Elon, support other developers of AI and robotics.

Advocate for space investment – Public support matters. Contact policymakers, push for increased funding in space exploration, and demand transparency on corporate-led missions. Public interest can drive political will.

Share your thoughts in the comments below or at the Quests Community.

Complete this quest—there’s no right or wrong way to complete it!—log it @ the Quests Community, and you’ll earn the Tower badge on your adventurer profile.

And, as always, thanks for reading!