The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, Thomas Moran, 1872

Welcome back to Quests.

Last week we were glued to the couch playing Balatro; this week we’re leaving town and exploring the outer limits of what’s known.

This is what animates Quests: pushing at the boundary of our daily habits, expanding idle discourse into adventurous action.

Gather your belongings, and let’s set out for green and pleasant lands.

In 1893, the historian Frederick Jackson Turner presented his famous “Frontier thesis.” If you were to make a shortlist of the most impactful essays of all time, Turner’s would be near the top. It influenced generations of American historians and remains a mainstay of high school and college curriculums.

Presenting to his peers at the American Historical Association, Turner argued that the American character was fundamentally shaped by the experience of Western expansion and the challenges of settling the frontier.

It was a simple, succinct idea:

From the conditions of frontier life came intellectual traits of profound importance. [...] That coarseness and strength combined with acuteness and inquisitiveness; that practical, inventive turn of mind, quick to find expedients; that masterful grasp of material things, lacking in the artistic but powerful to effect great ends; that restless, nervous energy; that dominant individualism, working for good and for evil, and withal [sic] that buoyancy and exuberance which comes with freedom—these are traits of the frontier, or traits called out elsewhere because of the existence of the frontier.

Pioneering Americans forged a new nation; they were scrappy individualists, common capitalists. They settled the land, and the land settled them. There’s an air of geographic determinism in Turnerian thought; the frontier itself—literally and figuratively—made us who we are.

But, even in Turner’s time, the world had shifted. In the face of modernizing forces, Turner struck an elegiac tone. The frontier was closing, and with it, the wellspring of the American spirit.

As Turner put it: “And now, four centuries from the discovery of America, at the end of a hundred years of life under the Constitution, the frontier has gone, and with its going has closed the first period of American history.”

Turner’s big idea hasn’t gone unchallenged. It’s been critiqued as a just-so story, a convenient tale that erases the brutal realities of colonization, displacement, and exploitation.

But, despite its flaws, Turner’s thesis still resonates. It stirs something in us. More than ever, we yearn for the gravitational pull of the new and the unknown. We understand that whatever we strive for at the edge of our existence—what Jean Paul Sarte called our “fundamental project”— defines who we are at our core.

To this point, there’s a subtle adjoinder at the end of the Turner quote above—did you catch it?

“Or traits called out elsewhere because of the existence of the frontier.”

The mere existence of the frontier—a space to expand into, to imagine oneself—motivates people.

JFK knew this. Nearly seventy years after Turner’s presentation, John F. Kennedy revived the idea of the frontier, repackaging it for a post-WW2 America as “The New Frontier.”

In 1960, Kennedy gave a speech to the Democratic National Convention in which he framed his bold policies under this Turner-inspired banner:

I am asking each of you to be new pioneers on that New Frontier. My call is to the young in heart, regardless of age—to the stout in spirit, regardless of party.

“The young in heart,” “the stout in spirit.” It’s hard to imagine a president speaking like this today.

After all, no frontiers remain. The stars are out of reach; the culture is stuck in algorithmic loops. And so we make faux-edgy memes about our predicament.

Frankly, I’m annoyed by this attitude. I have little patience for cynics, pessimists, and catastrophizers. Rather than wallow in performative despair, we should do our best JFK impression and ask ourselves, without irony (as difficult as that may be): What can I do? Where can I go?

Let’s start close to home.

Here Frontiers

For a few years in Louisiana I lived directly across from a patch of woods: maybe twenty or thirty acres that sat undeveloped between neighborhoods.

But I never went in them. They were just woods.

This treatment of everyday surroundings as “non-places” underlies much of our experience today. It’s like the videogame mechanic that features in many strategy games—the Fog of War—in which undiscovered parts of the map are blacked out, so that even what’s right next to our homebase is enshrouded in darkness.

Fog of War featured in Command and Conquer: Red Alert 2

But here’s the thing: we know what’s in the black spots. And it’s not bad guys or a pot of gold.

It’s a tangle of trees and underbrush. Strip malls that all look the same. Miles and miles of private property—strangers’ houses, corporate-owned farmland, gated office parks—where we aren’t meant to set foot.

So there’s no real curiosity about these undiscovered-to-us places. Who cares, who even has the time, to explore what’s already been divvied up, built on, and rented out?

Here’s what I want to suggest: we need to find ways to reinvigorate physical spaces, to make them feel new and revitalized, to tickle our reward systems and get us excited about what’s around the corner.

One option is geocaching—a kind of modern-day treasure hunt that uses GPS to guide participants to hidden containers, or “caches,” tucked away in the world around us. These caches, placed by other geocachers, might contain small trinkets or a logbook to sign.

Jeremy Irish, the founder of Geocaching.com, created the organization in 2000, when GPS technology was becoming accessible to the masses. Irish gradually turned a niche idea into a global movement. Today, there are more than three million active geocaches worldwide. Check out their website to find caches near you.

Augmented reality (AR) mobile games are another exploratory driver. Remember the summer of Pokemon Go? It was a short-lived phenomenon, but for a few glorious months I was out there. I trotted through parks and parking lots, hunting down Charizard and battling thirteen-year olds. (That’s normal, right?)

I’d love to see similar games take off. The idea of overlaying the real world with motivating challenges is simply too good to ignore. And there are other applications for AR apart from mobile games.

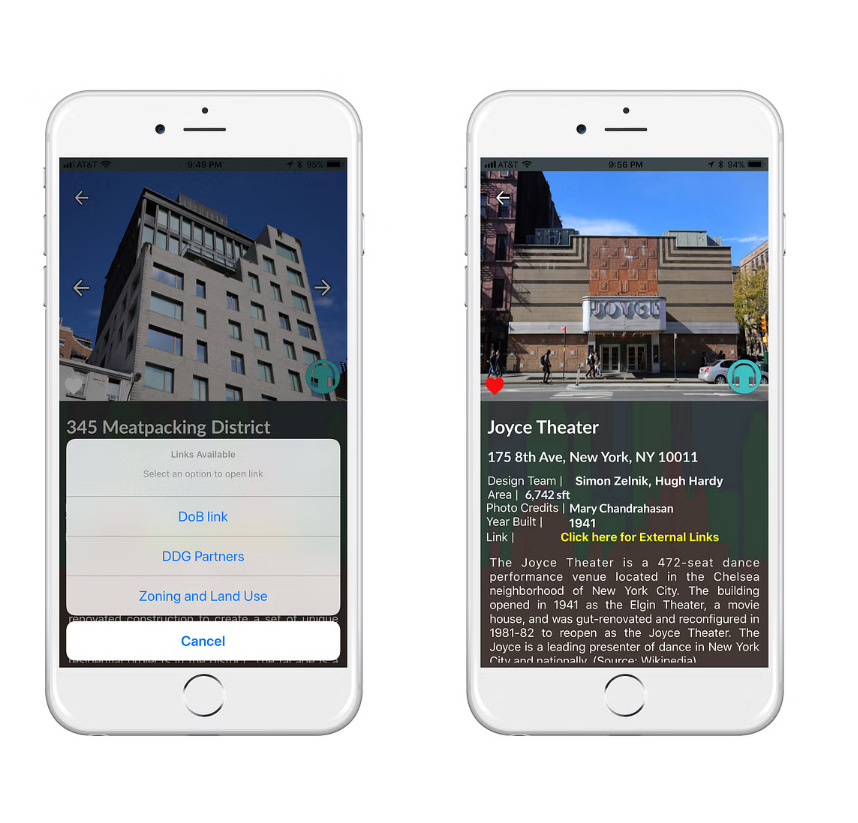

If you ever visit NYC, LABYL (“Learn About the Buildings You Love”) is a fantastic app catering to architecture lovers. Here’s how their website describes the project:

“LABYL is an architectural mobile application that allows users to identify buildings that interest them, simply by taking a photo of the structure with their phone. The app is designed to pair the user’s picture to images in the database. Users whose interests are piqued from the instantaneous architectural discovery can further explore the neighborhood for similar buildings.

It works surprisingly well; I used LABYL a few times walking through the city, and it really incentivized me to look up and notice the architectural variety overhead.

LABYL

This is the promise of augmented reality, pulling history and intriguing facts directly into our awareness: anything to puncture the surface tension of our everyday bubbles.

The challenge with technology is that, for all its benefits, it also muddles our spatial experiences and offers an attractive alternative to going anywhere at all. We have exploration at home.

Virtual Frontiers

Fundamentally, technology is both short circuiting and fulfilling our exploratory impulses It’s a frontier killer—and a frontier in itself.

The 90s dream of the world wide web—a wild, open expanse of creativity and connection—feels largely unrealized, replaced by platforms that entrap us in repetitive, predictive behaviors.

Consider social media. Often described as a “landscape,” social media may seem like an open space—an anything-goes, whatever-you-like phantasmagoria of sight and sound— but in practice it’s a closed system. The rules of engagement are baked into the medium itself: vertical scrolling, algorithmic recommendations, and content designed to keep you clicking whatever you’ve clicked before.

Nothing about Instagram or TikTok excites the imagination. They’re not “for” anything beyond momentary distraction. The qualities of frontier consciousness outlined by Turner—practicality, inventiveness, “buoyancy and exuberance”—are not fostered or found here.

Until a new type of platform comes along—one designed for real discovery and thoughtful engagement—social media feels like a closed frontier. It’s too static, too circular. So where are people exploring, creating, and pushing into new worlds?

For many, the frontier now exists in open-world video games.

Open-world games are sandboxes where players can roam freely and decide how to engage with the environment. Unlike linear games, which guide players “on rails” along a set path, open-world games encourage exploration and creativity.

The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild

Today, open-world playgrounds dominate gaming; best-selling titles include Grand Theft Auto, Minecraft, and Red Dead Redemption. There are more than three billion video gamers worldwide. Kids congregate in Fortnite and Roblox; the Metaverse has become their third place.

At this point, you can probably guess my own thesis à la Turner: open-world games are where many people now find exploratory fulfillment, for better or worse. Games like Elden Ring and The Legend of Zelda are like massive interactive artworks; they feed into our sense of adventure and challenge us in ways that are irreplicable in daily life. They are becoming sublimely good.

And it’s early innings for these open, online worlds. Full photorealism, in which virtual landscapes are completely indistinguishable from reality, is on the horizon. User-generated content (UGC) is empowering players to create their own games with no-code or low-code tools. What used to take a team of developers months can now be built in an AI-assisted weekend. The frontier is yours to make.

Of course, there’s no substitute for the real world. As excited as I am about the possibilities of virtual frontiers, there’s a naturalist in me that still yearns for grass and water and air and light.

We have to balance these twin forces. On one side, the innovations and excesses of technology; on the other, the real spaces that must be protected and revitalized. It’s not an either/or decision.

My own pipedream is an open-world game that mirrors physical reality one-to-one. Imagine your town recreated digitally, where you can explore both the virtual and real versions of the same places—parks, shops, museums, libraries.

Kevin Kelly described a similar vision in his 2019 article about the Mirrorworld. He envisioned a digital layer overlaid onto the physical world, where augmented reality doesn’t replace reality but adds to it.

It sounds like science fiction, but the technology is nearly there. AR glasses, real-time 3D mapping, user-generated content: these will coalesce and create new frontiers— new edges of experience— in the public imagination.

In the process, we mustn’t lose sight of “the meadows and the woods and mountains; and of all that we behold from this green earth.” There is always more to discover—and rediscover—in the natural world.

Tintern Abbey

There are countless other frontiers that I haven’t covered here, economic and creative areas where entrepreneurs, scientists, artists, and academics are pushing forward.

I’ve listed some in the poll below; vote for whichever most interests you, and I’ll write a Quest on the winner in the new year.

In the meantime, get exploring!

Here’s Quest 9:

Explore a new frontier

Key Details

Explore physical “here” frontiers: discover a new-to-you location in your town, find a geocache, or play an AR game.

Check out virtual frontiers: discuss your favorite open-world game, create your own game using no-code tools in Fortnite or Roblox, or sketch out your own ideas for next-gen Mirrorworld content.

Complete this quest, log it @ the Quests Community, and you’ll earn an Explorer badge on your adventurer profile.

Recommended Reading

The Significance of the Frontier in American History

AR Will Spark the Next Big Tech Platform—Call it Mirrorworld

Right up my alley. You articulated many of my unfinished thoughts. I’d include Pokemon Go in the mix, not in the artful category but about exposing people to new experiences.