Ajax, John Steuart Curry, 1936-7

I’m pretty sure eating meat—the way most Americans do, most of the time— is unethical. But I’m not a vegetarian—far from it.

I’ve read about the intelligence of pigs, cows, even chickens, and their capacity for suffering. I’ve seen the images from the factory farms: grim living conditions, haunting eyes awaiting their slaughter. I’ve heard the screams from the kill floors.

Still, my caveman brain sees the portrait of Ajax the cow and thinks: That’s some prime beef right there. A juicy ⅓-pound patty, extra cheese, bacon piled on. Yes, I’ll have fries with that.

I have driven many miles and walked many steps to reach a Popeyes or a KFC. I’ve savored grilled steaks with family, red wine in hand, and thought, in a blissful haze of gratitude: This is good.

Nowhere else in my life do I encounter such a gulf between my brain and my gut, between what I think intellectually and what I feel instinctually. It’s a dilemma as old as human civilization. How do we reckon with it?

Let’s go to the Library and gather resources—here in one place—to think intelligently about eating animals.

We’ll dive deep into the debate, leaning on thinkers like Peter Singer and Roger Scruton as we ask the question: is it wrong to eat animals in today’s world? If so, why?

We’ll consider how cheeseburger lovers like me can eat less meat and be more conscious when we do. We’ll peek at the future too: real meat grown in labs, no animals harmed.

Bring a snack—maybe skip the beef jerky—and let’s dig in.

The Meat Eaters

Humans have been eating animals for 2.4 million years. According to one of the most persistent theories in anthropology, eating meat made us human: nutrient-dense animal flesh fueled the evolutionary development of our brains. As Katherina Menne put it in Scientific American:

Many people today justify their excessive meat consumption to themselves and others with these arguments. Modern man is a born meat eater, they reason, as a glance at human history shows. What's more, the mastery of fire, the development of language, the origin of the division of labor, the beginning of social hierarchies and even the emergence of culture could be related to hunting and eating meat. Accordingly, the consumption of meat is a natural need of humankind whereas vegetarianism is unnatural and possibly even harmful to health.

We are animals, animals are animals, and it’s perfectly natural for us to all eat each other. It’s the way things are. Charles Darwin, without ever meaning to, made this logic airtight. By placing humanity not above but within the natural order, he removed any cosmic guilt: eating animals was no more morally fraught than lions taking down a gazelle.

What’s more, eating meat is deeply embedded in our cultural and religious traditions. Biblical scripture portrays offerings of lamb and the consumption of flesh as acts sanctioned by divine will. The feasts of antiquity, from Homeric banquets to the communal hunts of indigenous peoples, elevate meat to a symbol of sustenance and social cohesion. Together we break bread, drink wine, and partake in the bounty of the land.

But intuitively we know something is amiss here. When I greedily take down a Big Mac and fries from behind the wheel of my SUV, there’s no symbolism in the act, no social value, only an unseen trail of the machinery of capitalist production: labs, factory farms, freeways, freezers, fryers.

It’s gluttony, plain and simple. We know it, and our predecessors knew it. “Be not among winebibbers; among riotous eaters of flesh: For the drunkard and the glutton shall come to poverty: and drowsiness shall clothe a man with rags.” — Proverbs 23:20-21.

The naturalistic argument falls apart entirely when we consider that humans have historically engaged in all sorts of behaviors once considered “natural” but that we’ve since come to see as monstrous: violence, slavery, the systematic mistreatment of entire groups of people.

Our moral landscape shifts. It evolves. Which brings us to Peter Singer, who’s done more to shape modern ethical debates than anyone else alive.

The Calculus of Suffering

Peter Singer is a philosopher and a provocateur. He is, at times, annoyingly rigid in his ethics, like the straight A kid in school who could do no wrong.

He’s a utilitarian, meaning his ethical system is built on maximizing the greatest good for the greatest number. Applied to the modern treatment of animals, this leads to one of the most searing critiques of human civilization in the last century. It’s simple math: Singer argues that the suffering of billions of factory-farmed animals outweighs the pleasure humans gain from cheap meat.

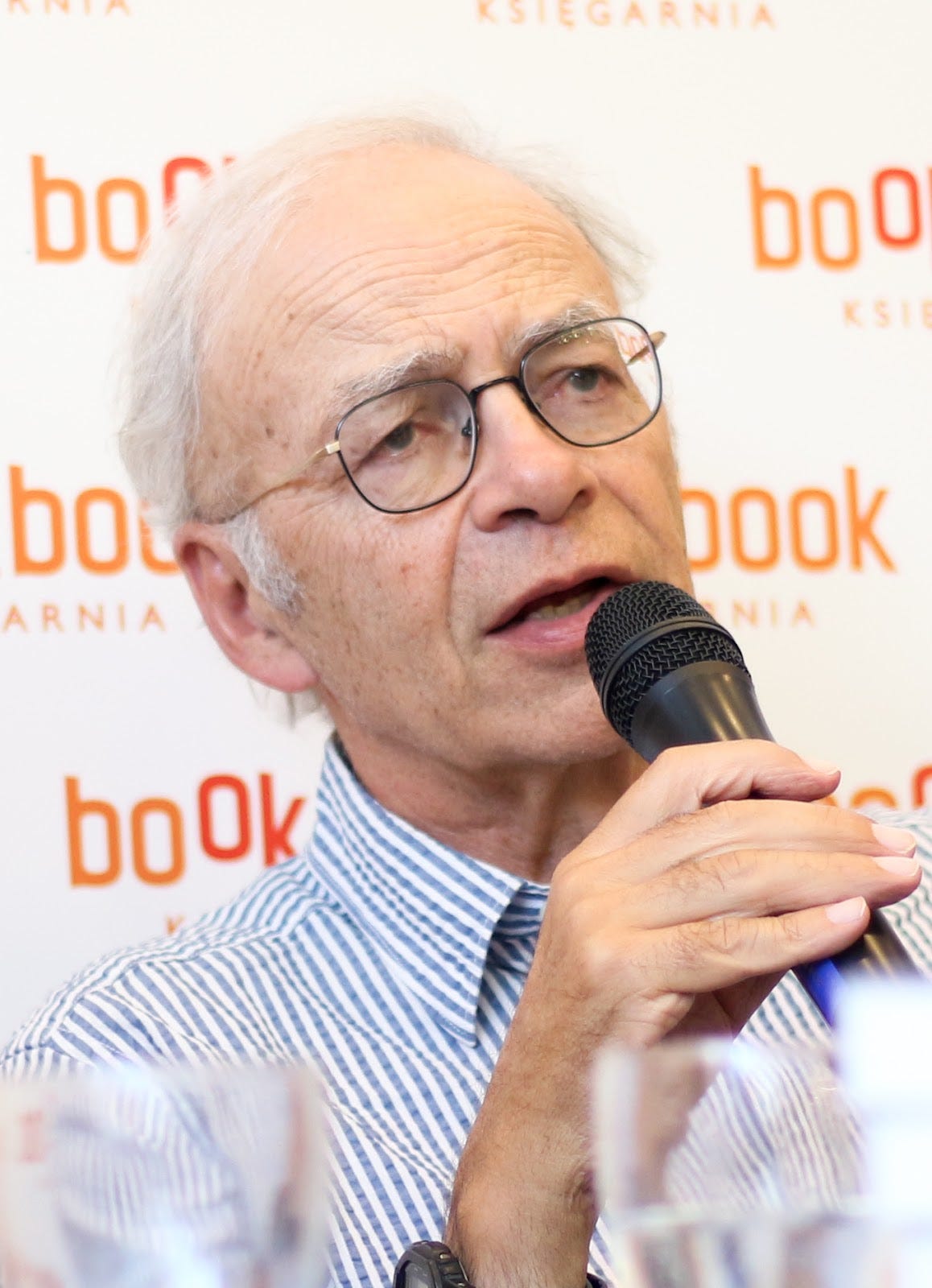

Peter Singer

His 1975 book Animal Liberation channels the great English philosopher and founder of utilitarianism Jeremy Bentham, who famously said about non-human animals: “The question is not, Can they reason? nor, Can they talk? but, Can they suffer?”

Singer says they can, and they do. Not only that, he shows us. He’s an excellent writer, who lays out cold, brutal, horrifying facts that accumulate in an open reader’s mind. Like Noam Chomsky, he overwhelms you with information, a relentless barrage of inconvenient truths.

Here are just a few:

Over 70 billion land animals are slaughtered for food each year, the vast majority in factory farms.

Countless chickens, who make up the vast majority of all farmed animals, spend their entire lives in cages so small or so crowded they cannot spread their wings.

Pigs, considered at least as intelligent as dogs, are raised in cramped, stressful conditions before they’re turned into ham and bacon.

Cows in the dairy industry are forcibly impregnated, their calves taken at birth so humans can consume the milk intended for them.

Animal agriculture is responsible for around 14.5% of global greenhouse gas emissions.

Chicken-nuggets-to-be

You don’t need a philosophy degree to appreciate that factory farming is unethical. But what about animals raised differently?—the happy cows, chickens, and pigs who live out their lives in green fields under blue skies? Better, according to Singer, but still wrong.

Even in these idyllic settings, Singer holds that killing animals for food remains problematic. If they’re sentient—capable of joy, fear, or attachment—ending their lives cuts short their potential for well-being, tipping the utilitarian scale.

Here is where Singer’s utilitarianism can begin to veer into strange territory. Elsewhere, Singer has argued that parents should have the right to euthanize severely disabled infants if their quality of life is projected to be too low. He’s suggested that any discretionary spending that doesn’t go toward the maximum alleviation of suffering is unethical—meaning your Netflix subscription is a moral failing since it could have been spent on mosquito nets to prevent malaria in Africa.

His strict utilitarian logic forces him into uncomfortable positions, as illustrated by the classic trolley problem: a runaway train is about to kill five people unless you flip a switch that reroutes it toward one person instead. For Peter Singer, you pull the lever every time—even if that one person is your sibling and the five are strangers. In his view, maximizing overall well-being overrides personal bonds.

Critics dismiss such ethical rigidity with the “demandingness objection”—Singer’s system asks too much, stretching moral duty to a breaking point. This makes for great fodder over at Existential Comics, which never fails to succinctly parody Western civilization’s greatest philosophers. But even if we don’t fully subscribe to Singer’s ethics, he does make a compelling case against our mindless consumption of meat.

What about the other side of the equation? How might we defend the act of eating animals in light of Singer’s relentless critique?

Eating Our Friends

Roger Scruton, the late British philosopher known for his conservative, cantankerous attitude toward basically everything, took a more traditional approach to the ethics of meat-eating.

Roger Scruton

In his essay “Eating Our Friends,” Scruton doesn’t deny that factory farming is immoral; he plainly condemns any system that treats animals as raw commodities to be exploited. But where Singer concludes that all meat-eating is inherently wrong, Scruton argues that it’s not the mere act of eating animals that’s unethical, but how we raise, care for, and ultimately kill them.

“A great number of animals owe their lives to our intention to eat them,” Scruton points out. For millennia, humans have hunted and raised animals for food, integrating them into complex ritualistic ceremonies. Fast food culture and factory farming pave over these “moral and spiritual realities,” the cultural processes by which we sustain ourselves.

For Scruton, we have a “duty of care” to treat animals with dignity and act as “conscientious carnivores.” He offers the traditional farmer as an example:

Consider the traditional beef farmer, who fattens his calves for 30 months, keeping them on open pasture in the summer, and in warm roomy barns in the winter, feeding them on grass, silage, beans and maize, attending to them in all their ailments, and sending them for slaughter, when the time comes, to the nearby slaughterhouse, where they are instantly dispatched with a humane killer. Surely, such a farmer treats his cattle as well as cattle can be treated. Of course, he never asked them whether they wanted to live in his fields, or gave them the choice of life-style during their time there. But that is because he knows — from instinct rather than from any philosophical theory — that cattle cannot make such choices, and do not exist at the level of consciousness for which freedom and the lack of it are genuine realities.

Not all killings are equal, according to Scruton, and there’s no simple moral calculus to be performed here. Ultimately, we “should not abandon our meat-eating habits, but remoralize them, by incorporating them into affectionate human relations, and using them in the true Homeric manner, as instruments of hospitality, conviviality and peace.”

“Eating our friends” can be consistent with deep respect and empathy—provided we honor the animal’s life, minimize suffering, and root the act of meat-eating in community, ritual, and gratitude.

Eating Less Meat

To be honest, even after reading Singer and Scruton, I struggle with where I land here. Free-range beef and pasture-raised poultry feel acceptable under specific conditions. Eating pigs at all feels wrong under almost any circumstances, given their intelligence and emotional capacity. And I’m painfully aware that I’m completely removed from the actual killing of animals; we’ve compartmentalized their suffering, distanced it from ourselves, placed it behind doors we’ll never open.

Despite these uncertainties, it seems clear to me that we should all eat less meat. The benefits are too obvious to ignore. Less meat means fewer calories from dubious sources, a smaller carbon footprint, and—as Singer would say—less suffering in the world, even if only at a marginal level.

One solution is embracing more meatless meals. Fruits and veggies, whole grains and starches, and, for the “But mah protein!” crowd, it’s easy to overcome that with beans, lentils, and plant-based protein sources.

If your answer is “basically none,” I’d challenge you to try one or two. If you’re a lifelong carnivore, it won’t be easy, but it’s also not as boring as it sounds. We crave meat largely because we’re used to it, like a sweet tooth or a penchant for alcohol. That craving is a habit, and habits can be changed.

Finally, there’s a new frontier that may solve the ethical dilemma once and for all: lab-grown (or cultured) meat. Companies like Upside Foods and others are racing to produce real animal flesh without the needless slaughter.

New meat, cultivated directly from real animal cells

It might be a while before the price is competitive, but if (hopefully when) it is, we’ll have wide access to the taste and texture of meat without the guilt—or the nagging uncertainty about whether even “cage-free” or “free-range” animals lived the lives we imagine.

Our journey is almost complete. I hope I haven’t ruined your appetite, but these are timeless philosophical questions worth grappling with. Now it’s time to put all of this into practice.

Here’s Quest 15:

Eat less meat

Key Details

Embrace meatless meals: swap out a meal for a plant-based alternative, share a recipe in the comments, or keep a short dietary journal.

Choose ethically-raised meat when you do eat it: seek out local farms, sustainable restaurants, or trusted labels (e.g., pasture-raised, grass-fed).

Support access to cultured meat: Sign the petition to ensure access to cultured/cultivated meat in Florida and Alabama, where it’s currently banned.

For more books on the subject, check out:

The Omnivore’s Dilemma by Michael Pollan:

Were the walls of our meat industry to become transparent, literally or even figuratively, we would not long continue to raise, kill, and eat animals the way we do.

Eating Animals by Jonathan Safran Foer:

Perhaps in the back of our minds we already understand [...] that something terribly wrong is happening. Our sustenance now comes from misery. We know that if someone offers to show us a film on how our meat is produced, it will be a horror film. We perhaps know more than we care to admit, keeping it down in the dark places of our memory-- disavowed. When we eat factory-farmed meat we live, literally, on tortured flesh. Increasingly, that tortured flesh is becoming our own.

Should We Eat Meat? by Vaclav Smil:

Meat eaters don't like me because I call for moderation, and vegetarians don't like me because I say there's nothing wrong with eating meat. It's part of our evolutionary heritage! Meat has helped to make us what we are.

Join me in trying to eat more mindfully, and thanks for reading!