Build A Better Athlete

Playing god to win the gold

“A lot of people say they’re worried about changing our genetic instructions. But those [genetic instructions] are just a product of evolution designed to adapt us for certain conditions that may not exist today. We all know how imperfect we are. Why not make ourselves a little better suited to survival?’ [...] That’s what we will do. We’ll make ourselves a little better.”

Nobel laureate James Watson as quoted in The Gene: An Intimate History by Siddhartha Mukherjee

“His quads are the size of my waist & upper body. I’ve never seen anything like it. I don’t often stare at another man’s legs, but in that case, you can’t help it.”

Former Giants quarterback Eli Manning on Saquon Barkley

We have a peculiar vocabulary for describing our greatest athletes. We talk about freaks, specimens, beasts, and monsters. We’ll say: “Oh, she’s jacked!” or “ripped” or “shredded.”

You can be built like a tank, a Mack truck, or a brick shithouse.

There are grown men, men amongst boys, and absolute units.

My favorite moniker growing up in Texas—where people draw on horse metaphors to describe pretty much everything—was hoss, a term of endearment reserved only for the biggest, meanest, and fastest linebackers and running backs.

Saquon Barkley is a prototypical hoss, as Eli Manning clearly noticed.

Saquon Barkley

But what’s in a hoss? Are they born or made?

Can you or I or my friend’s kid who’s a pretty damn good baseball player and might even play D1 ball—can we mere mortals reshape ourselves into the freaks, beasts, and monsters we see on TV? Can we make ourselves a little better?

It’s a quest that’s consumed many: to enhance mind and body in the pursuit of greatness.

When good ol’ fashioned hard work is the method of enhancement, everyone approves. Genetics being what they are—until they aren’t; more on this in a minute—we tend to hold in highest esteem the behaviors and habits that competitors can actually control to better themselves: spending hours in the weight room or on the treadmill; fending off carbs like they’re poison and ingesting protein like it’s oxygen; in a word, grinding—with Sisyphean determination—into peak physical form.

But there are shortcuts: old drugs (magical potions of stimulants and hallucinogens) and new (from adderall to anabolic steroids). Many of us have an almost instinctive aversion to such chemical hackery; it’s the same distaste the gym goer feels for their overweight neighbor who took Ozempic and dropped fifty pounds without really “earning it.”

Soon there will be more shortcuts and better shortcuts—shortcuts that can change our very biology, perhaps even before we are born.

Let’s venture into this strange new territory and glimpse a few possible futures for sports.

Performance Enhancing Drugs—Then and Now

Athletes have always looked for an edge. Ancient Olympians consumed hallucinogenic mushrooms to enhance their abilities. Incan runner-messengers, known as chasquis, chewed coca leaves to increase their energy and stamina. In the 19th and 20th centuries, professional cyclists and other endurance athletes frequently used “dope”—a term that’s now all too familiar—consisting of various concoctions that often included caffeine, cocaine, and even opium to fight off fatigue during grueling multi-day races.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, baseball was at the height of its steroid era: the use of anabolic-androgenic steroids (AAS), synthetic derivatives of testosterone, was widespread. Players injected performance-enhancing drugs to dramatically increase muscle mass and reduce recovery time. They hit a lot of home runs.

And many fans loved it! They weren’t particularly fussed by concerns over the record books, “uneven playing fields,” or player’s health. Sports are entertainment, after all, and shouldn’t professional athletes be free to self-optimize however they see fit?

That’s the perspective of Aron D’ Souza, the founder of Enhanced Games, whose mission is to “to redefine super humanity through science, innovation and sports.” It’s the Olympics on steroids—literally. The plan is to feature big-ticket events—track, swimming, weightlifting—and let athletes show what’s possible when the rulebook gets tossed and doping isn’t merely allowed but openly encouraged.

Aron D’ Souza

Here’s Barney Ronay describing Enhanced Games in The Guardian:

The basic premise is simple and reliably shocking. What if we just removed all barriers to taking drugs in sport? What if we rewarded and celebrated drug-assisted achievements, explored the wild frontier of juiced-up human potential, and introduced newer, kinder language to destigmatise the unfairly marginalised drug-taking community, so dopers become “Enhanced,” non-dopers “Natural,” supporters and consumers “Allies?”

D’Souza has secured millions in seed money from big-name venture capitalists, including Peter Thiel. He’s openly courting disgruntled Olympians and high-profile athletes, promising them a payday and a platform free from moralizing. In his article for the Guardian, Ronay calls it shameless, grotesque “bullshit,” “a way of completely misunderstanding the point of sport, replacing things like narrative, emotional connections, human failure as well as human success with the most furiously literal-minded, outcome-based version, sport as reimagined by a particularly dull robot, sport as a pornography of human performance.”

In spite of its critics, the Enhanced Games will premier—where else?—in Las Vegas in May 2026. Maybe the stigma around performance enhancing drugs is slowly evaporating, as it did with the use of cannabis or the rise of sports gambling. If everyone’s enhanced (i.e., on PEDs) and everyone knows that everyone’s enhanced, then what’s the problem?

It seems there’s something about drugs that short-circuits our moral calculus. Even if we accept some enhancers, we recoil at others. The newscaster who takes a daily beta blocker to kill their nerves is simply “managing anxiety.” The programmer who microdoses psilocybin is “optimizing focus.” The graduate student popping Adderall is “studying hard.” We tend to draw blurry, convenient lines between therapy and enhancement. But a linebacker injecting testosterone is, for many, a glowing line in the sand.

Which is why D’Souza’s games will likely remain a sideshow, for now. Sports featuring nothing but roided-up athletes is a bridge too far for the mainstream. It feels wrong, and maybe it is.

But what if the means of enhancement wasn’t an injection but a biological edit? What if you could achieve physical and mental superiority not by intaking a substance but by altering the body’s own instruction manual?

Gene Doping

In the early 2000s, two research teams—one led by H. Lee Sweeney at UPenn, the other by Ronald Evans at the Salk Institute—were developing gene therapies to treat muscle-wasting diseases and metabolic disorders.

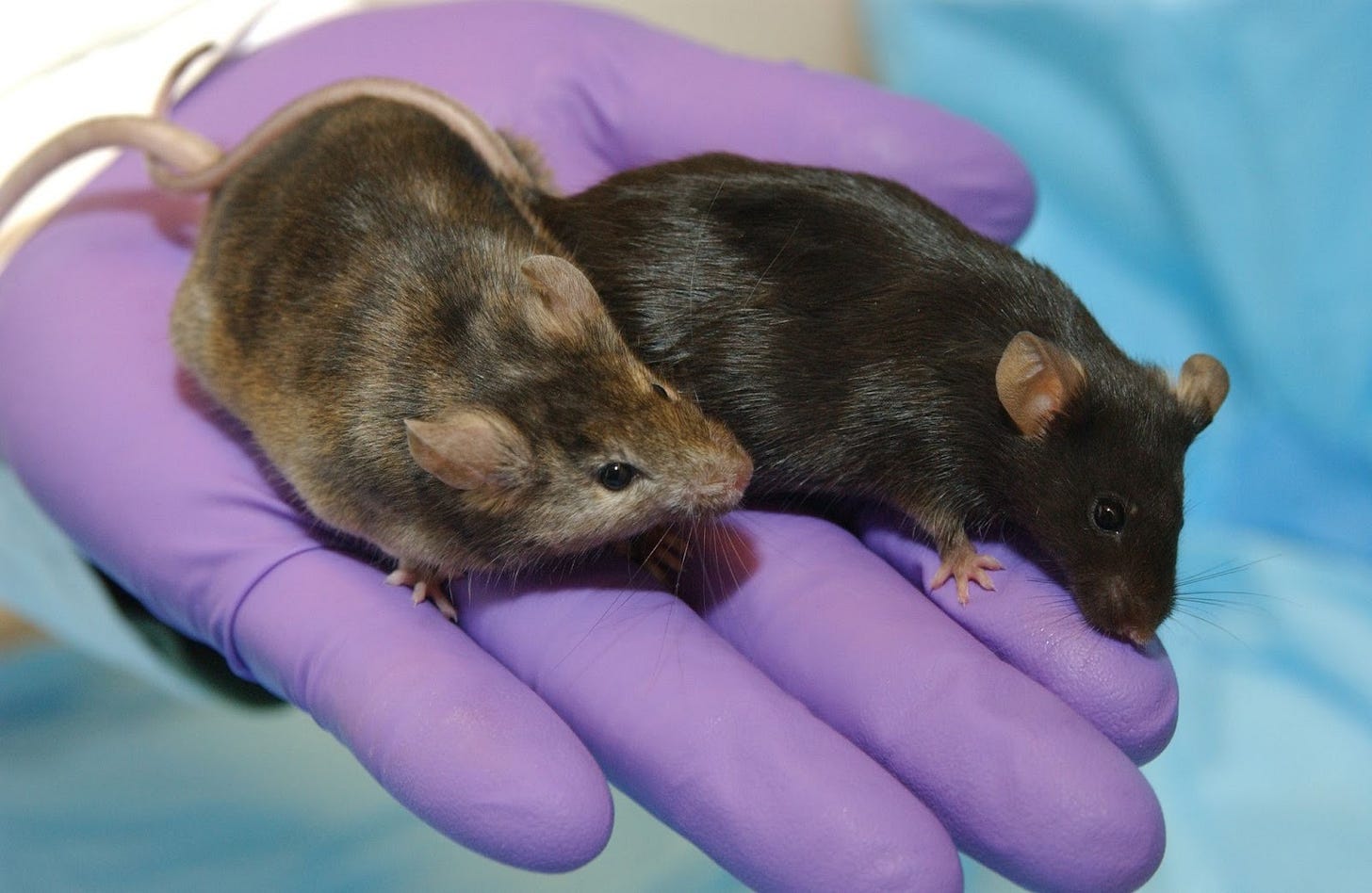

Sweeney’s lab discovered that inserting a gene for IGF-1, a growth-promoting protein, into mouse muscle reversed degeneration and increased mass by nearly 40 percent. The media dubbed them “Schwarzenegger mice.”

Evans’s group went in another direction, engineering “Marathon mice” whose altered PPAR-delta gene lets them burn fat more efficiently and run twice as far as normal.

Genetically modified mice

It should come as no surprise that the researchers were “inundated with requests for [gene doping] from professional weight lifters and numerous other athletes.” The sports regulatory community responded swiftly.

In 2003, the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) stepped beyond its usual scope to preemptively ban genetic modification in athletes, calling it “gene doping,” an odd turn of phrase since genes aren’t exactly dope. WADA justified the ban by citing the need to protect “natural talent” and ensure a level playing field. Sounds reasonable enough, right?

Not to some. In their paper “Regulating Genetic Advantage,” Sarah Polcz, a professor of Law at UC Davis & Anna C F Lewis, a bioethicist at Harvard, argue that “doping” is a loaded term and that what society considers “natural talent” is itself the result of a genetic lottery—a matter of luck in inheriting certain genes. In their view, “genetic modification is a tool to reduce the inequities of the natural lottery.”

In other words, we are all thrust into the world with a complex polygenic makeup that none of us chose, and if technology can safely and reliably close the gap between, say, the Kalenjin tribe of Kenya, whose unique physiology enables them to dominate long-distance running, and the rest of the elite marathon running community, well, wouldn’t that be fair?

And lest you think this is academic posturing and surely no one actually supports genetically modifying athletes, Polcz and Lewis found that 54% of the public agreed or were indifferent to allowing athletes who chose to acquire a genetic enhancement to race against those who had not. Leveling the playing field, indeed. It’s revenge of the nerds.

While gene modification in sports may seem a remote possibility, it’s technically quite feasible: these tools are already helping people in clinical contexts.

We should be precise about the terms here. “Gene therapy” is a broad, overarching goal for many researchers: treating a disease by altering a person’s genetic material.

The “Schwarzenegger mice” are a classic example of one method of gene therapy, often called gene addition. In that case, researchers used a modified virus as a tiny delivery truck to shuttle a new copy of the IGF-1 gene into the existing muscle cells.

A newer and far more precise method is “gene editing,” which uses tools like CRISPR-Cas9. Instead of just adding a gene, CRISPR acts like molecular scissors, allowing scientists to go into the DNA and make a specific change—to cut, delete, or replace a specific genetic sequence.

Here we have to make a truly crucial distinction between somatic versus germline editing. Somatic gene therapy (using either method) targets the body cells of a single, living person—their blood, muscles, eyes, etc. The changes are not inherited and die with the patient. This is happening right now.

The new FDA-approved therapy Casgevy is a great example. Doctors remove a patient’s own blood stem cells, use CRISPR to edit the faulty gene that causes sickle cell disease, and then re-infuse the corrected cells back into the patient, offering a functional cure. Similar somatic therapies are in advanced trials for hereditary blindness and muscular dystrophy.

Kendric Cromer, the first sickle cell gene therapy patient

Germline gene editing, on the other hand, involves modifying an embryo, sperm, or egg. These are reproductive cells, so the changes are permanent and heritable—they would be passed down to all future generations. This opens a massive ethical and philosophical Pandora’s box—more on that in just a moment.

For now, it’s easy enough to see how these tools could be co-opted for athletic enhancement. An athlete could use the older gene addition method to insert a new gene into their muscles to increase mass and speed recovery. Or they could use the newer gene editing method to make precise changes: they might edit a gene to boost endurance and fat-burning, or disable a natural inhibitor to achieve extreme muscle growth.

Beyond physical enhancements, there’s potential for cognitive improvements. Just this week Aaron Rodgers wowed reporters with his ridiculous memory, reciting play-by-play moments from a game that happened in 2009. LeBron James has demonstrated similar abilities of “total recall;” so has Tom Brady and many elite golfers. Their ability to draw on a wellspring of memories represents a profound processing advantage.

What if that ability could be democratized? Researchers are already identifying genes linked to memory and neural plasticity. It’s plausible that somatic therapies could be developed to enhance the expression of these genes, not just to fight Alzheimer’s but to boost the baseline cognitive function of an athlete—improving their ability to read a defense, memorize a playbook, or make split-second decisions.

We’ll return to the far more ethically tangled world of germline editing in a moment. But what if enhancement was possible without any editing? What if we could forego the genetic hackery altogether and simply select for the most athletically promising traits from the very beginning?

Embryo Screening and IVF

IVF is now responsible for over 2% of all births in the United States, a number that continues to climb. Donald Trump has nicknamed himself (among other things…) the “fertilization president.” He recently announced policy changes making in vitro fertilization — “in glass,” as opposed to in vivo, “in the body” — more affordable. Every day, parents using IVF already select embryos based on basic genetic health, screening for devastating single-gene diseases. It’s only a small leap to imagine them selecting for other things—not just health but height, intelligence...or athleticism.

This is the future being paved by companies like Noor Siddiqui‘s Orchid. They offer “polygenic risk screening,” which analyzes embryos not just for single-gene diseases but for complex, multi-gene traits. For $2500 an embryo, “Orchid sequences over 99% of an embryo’s DNA, while alternatives sequence less than 1%”. For now, the company’s marketing is focused on the noble goal of screening for risks like Alzheimer’s or schizophrenia.

Noor Siddiqui

The same technology could just as easily be used to screen for desirable traits. New York Times columnist Ross Douthat recently had a fascinating and contentious back-and-forth with Siddiqui, pressing her on this very point.

If you can screen out a high risk for cognitive decline, it stands to reason you could “screen in” a high probability of cognitive giftedness or athletic ability.

Here’s what Douthat had to say: “Most people’s expectation is that if you can figure out what polygenic scores mean for diseases, you’re going to be able to figure out what polygenic scores mean for athleticism, for intelligence, to say nothing of a whole host of superficial traits.”

He continued, “If this technology works as well as you say it does, then you are essentially advancing toward a future where there will be a caste system in terms of how rich people versus poor people are genetically sculpting their offspring. Is your view that you are ushering in that kind of future?”

Siddiqui vehemently denied any such intention. The real inequality, in her view, already lies in who can access I.V.F. itself. “It’s a really sad history, I think, for the last 40 years that rich people get to have babies,” she responded, “and poor people who can’t afford I.V.F. don’t get to.”

In his book Ethics in the Real World, the moral philosopher Peter Singer struck a similar note when referring to genetic enhancements more broadly:

“Perhaps the best we can hope for is that wherever important enhancements, such as resistance to disease or the enhancement of intelligence (should it ever be possible) are available, they will be part of a basic healthcare plan so that everyone can benefit from them, and not only the rich.”

Other philosophers are more assertive in their evaluation of IVF, embryo selection, and enhancement. The philosopher Julian Savulescu has introduced the idea of “procreative beneficence.” In short, it’s the argument that parents have a moral obligation to have the “best” child possible.

Julian Savulescu

Applied to IVF and genetic screening, it means that if parents have the choice between several embryos, they have a moral obligation to select the embryo that, based on the available genetic information, is expected to have the “best life” or at least a better life than the others.

Savulescu argues that parents should select for non-disease traits that would give the child a better chance at a flourishing life, such as selecting for higher intelligence, better health, or, yes, athletic ability. He reframes genetic selection from a simple option to a moral duty.

Few would go that far. Ethical tripwires are everywhere. Some, like Douthat, are opposed to discarding viable embryos. Others recoil at the notion of positive selection and “designer babies”: the creeping feeling that we’re turning procreation into a high-stakes shopping trip.

But it’s not hard to imagine a world where this becomes normalized: first for health, then for everything else, including sports.

We all know how an arms race works. In the 20th century, we built nukes because the Soviets were building nukes (and vice-versa). Today, the same goes for drones, AI models, and—soon enough—our own biology.

All it takes is one geopolitical rival—say, ahem, China—to announce a program of genetically screened Olympic athletes, and things change overnight. Our queasy hesitations about “designer babies” could quickly evaporate. The moral high ground is cold comfort when you’re losing every gold medal.

The same might hold true for ambitious moms and pops. Once the technology is proven, embryo selection for athletic ability could become just another part of the exhausting optimization of modern parenting.

If the couple next door is screening their kid for a shot at a D1 scholarship—not just paying for elite travel ball and private coaching, but literally selecting for fast-twitch muscle fiber—how long do you hold out on “natural” procreation?

It’s a “Brave New World“ scenario, playing out one well-meaning (and likely well-off) parent at a time.

Then again, if this can be rolled out slowly, safely, and democratically—not now, but perhaps over the next few decades—is it truly a dystopia? If we can give every kid a better shot at an optimized life, then should we?

Which brings us to the final frontier: germline editing.

Human Germline Editing

This is Gattaca territory. We’ve talked about enhancing a single, living athlete (somatic editing), and we’ve talked about selecting the “best” embryo from a batch (IVF screening). But germline editing is a much bigger leap, potentially designing not just our descendants but our descendants’ descendants.

Let’s be clear on the difference. Embryo selection is still just high-stakes curation. You’re picking the “best” embryo from the genetic hand you were dealt. It tilts the odds, maybe even dramatically, but it’s still no guarantee. Germline editing, on the other hand, is about changing the hand itself—an act of creation rather than curation.

What is it exactly? Put simply, it’s the process of making precise changes to the DNA of reproductive cells using a tool like CRISPR. Because these are reproductive cells, the genetic modifications are not only permanent but heritable.

In his 2016 bestseller The Gene: An Intimate History, Siddhartha Mukherjee makes it clear that genetically modified humans are not some remote possibility; all the ingredients are already in place. He writes:

Consider the following steps in sequence: (a) the derivation of a true human embryonic stem cell (capable of forming sperm and eggs); (b) a method to create reliable, intentional genetic modifications in that cell line; (c) the directed conversion of that gene-modified stem cell into human sperm and eggs; (d) the production of human embryos from these modified sperm and eggs by IVF . . . and you arrive, rather effortlessly, at genetically modified humans. There is no sleight of hand here; each of the steps lies within the reach of current technology. Of course, much remains unexplored: Can every gene be efficiently altered? What are the collateral effects of such alterations? Will the sperm and egg cells formed from ES cells truly generate functional human embryos? Many, many minor technical hurdles remain. But the pivotal pieces of the jigsaw puzzle have fallen into place.

Mukherjee goes on to quote Rudolf Jaenisch, an MIT biologist, who said, “It is very clear that people will try to do gene editing in humans [...] We need some principled agreement that we want to enhance humans in this way or we don’t.”

Jaenisch was right. In November 2018, just two years after Mukherjee’s book, a Chinese scientist named He Jiankui shocked the world by announcing the birth of the first germline-edited babies, twin girls named Lulu and Nana. He had used CRISPR to edit the CCR5 gene in their embryos, attempting to make them resistant to HIV.

We still have no idea if the experiment was successful—that is, if the girls are actually resistant to HIV or, more importantly, what other off-target edits might have been made. The entire affair was shrouded in secrecy, enabled by a stunning lack of regulatory oversight in China at the time. For his part, He Jiankui was globally condemned, lost his job, and ultimately served a three-year prison sentence for illegal medical practices.

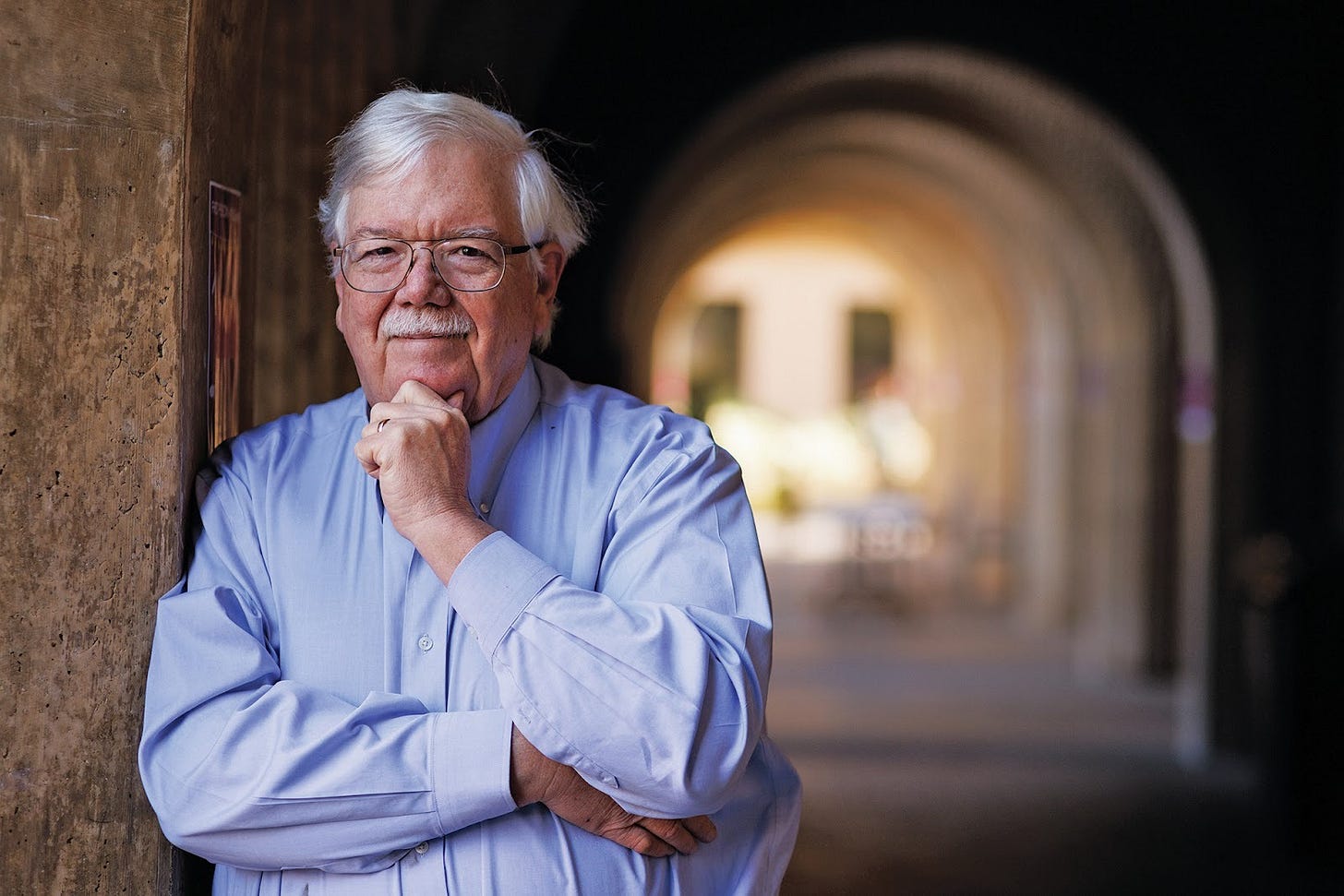

In his excellent book CRISPR People, the lawyer and bioethicist Henry Greely has written a compelling whodunit and medical explainer about Jiankui and the sheer absurdity of what he did.

Why was it absurd?

Greely lays it out. The “medical need” was non-existent: the father’s HIV was undetectable, and sperm washing already prevented transmission. The science was sloppy and dangerous, creating mosaic embryos where the edit didn’t even take in all their cells. The consent forms were a manipulative sham. And the potential benefit—HIV resistance—was trivial compared to the massive, unknown risks of making random, heritable changes to the human genome. It was a reckless, fame-hungry stunt.

Henry Greely

Even still, after spending hundreds of pages lambasting Jiankui, Greely poses the big question; in fact, he dedicates a chapter to it: Is Human Germline Genome Editing Inherently Bad?

His answer?

“No. At least, I don’t think so.”

Greely argues that the human germline isn’t a sacred, static essence of humanity. It’s “barely a thing at all,” a dynamic process that’s constantly changing. “There are, in fact, currently about 7.5 billion human germline genomes. Every living person has a ‘germline genome,’ and each one is different.”

We’ve been indirectly changing them for millennia. Widespread agriculture, for example, changed the selective pressures on our ancestors, favoring those who could better digest starch. The germline we have today is a product of human action, not just pristine “nature.” He argues that rejecting germline editing on the grounds of naturalness is a weak argument, one that would force us to “throw out a vast amount of our present civilization and medicine.”

The real questions, Greely suggests, are not about whether the technology is inherently evil but about its specific uses. We should be asking practical questions: Is it safe? Is it equitable? Is it being used for a good reason (like curing a devastating disease) or an arguably trivial one (like enhancement)?

In short, Greely believes we need to carefully regulate its application rather than ban the concept. As for a Gattaca-style arms race, he points out the biggest hurdle is technical: we simply don’t know of any single genes for enhancement (like a “smart” gene or a “fast” gene), making it a distant fantasy for now.

He points out that we currently don’t know of a particular gene for speed, intelligence, or what he calls “Scrabble ability.” These are incredibly complex traits governed by hundreds or thousands of genes interacting in ways we barely understand.

Therefore, the idea of germline editing an embryo to be “better” remains tenuous. You can’t just edit in the “fast gene” because it doesn’t exist. Instead, you’d be trying to make hundreds of precise, coordinated edits to an embryo’s source code, an act that is currently impossible and, given the risk of catastrophic, heritable side effects, wildly reckless.

What this means for the bottom line of enhancement in sports is clear: somatic editing and embryo selection are what will be debated and likely applied in our lifetimes.

Somatic editing is a much more plausible short-term scenario because it’s a blunt instrument, not a total redesign. A living, breathing professional athlete isn’t asking to be built as a perfect specimen—it’s too late for them anyway! They’re just looking for a single, targeted hack.

A weightlifter could, in theory, use gene therapy (doping?) to deliver a gene that disables the Myostatin inhibitor only in their muscles. This is a single, targeted edit to an existing system, much like the “Schwarzenegger mice.” It’s a far more realistic prospect for sports, as it bypasses the massive complexity of embryonic development.

Embryo selection—the polygenic kind—is the other, more immediate route. It cleverly sidesteps the “we don’t know what to edit” problem entirely. You don’t need to understand the biology; you just need to find statistical correlations.

If, for example, you had the genomes of 1,000 elite athletes, you could find the genomic patterns that are associated with elite performance. This is the future scenario where ambitious parents aren’t editing an embryo but simply selecting the one with the highest polygenic “score” for athleticism.

This conversation is obviously much bigger than sports. But sports provide a lens—perhaps the clearest lens imaginable—for seeing how this’ll all play out. The pressure to win is absolute; the results are public and unambiguous. For better or worse, it’s the perfect laboratory for the human arms race.

I’d be willing to bet that within a few generations, the sports landscape will be utterly unrecognizable. The “freaks” and “specimens” we watch today will look like amateurs, quaint relics from the all-natural era. The records will be rewritten. So will the rules.

This is where our philosophical ideals will slam into our competitive reality. It’s easy to oppose enhancement in the abstract. The concerns are obvious: How could it be regulated fairly? Won’t it permanently destroy the level playing field? Doesn’t it violate the very spirit of sport?

But the collective good is often at odds with what individuals want for themselves. Imagine it’s 2040, and you’re competing for a gold medal against athletes you know are enhanced. Or you’re doing IVF—which, in this future, practically everyone does because the benefits are too great to pass up—and you have the option to select for health traits that also happen to translate directly to athletic ability. Could you really say no?

For now, the regulatory environment, led by bodies like WADA, seems poised to prevent it. The word “doping” is powerful, and the line in the sand has been drawn. But as we’ve seen, that line is blurry, and the pressure from a geopolitical rival or even just the consumer market could erase it.

So, where do you stand? Should we proceed—cautiously, carefully—down the road of enhancement? Should we “make ourselves a little better,” as Watson suggested?

Or should we fight to stop enhancement in its tracks?

Path A: Enhance

(We should permit at least some forms of enhancement in sports, provided it is proven safe, regulated, and equitably accessible.)

Path B: No Enhancement

(We should ban all forms of enhancement in sports, fighting to preserve the natural human element of competition.)

You choose.

Our sports journey will conclude next week. As always, thanks for reading!

Thanks for writing this, it clarifies a lot. This exploraiton of human potential, from genetics to 'hoss' descriptions, is really fascinating and so important to consider.

A few things come to mind here:

1) In a world where you can edit away the downsides of inbreeding, would it still be immoral or icky for siblings or first cousins to have babies?

2) Maybe gene editing could help same sex couples have babies that share the DNA of both partners.

3) Maybe it could help us adapt to living in new environments like Mars more easily by withstanding heat or cold a bit better. I suppose the people that colonize Mars might need special skills to adapt and thrive there.