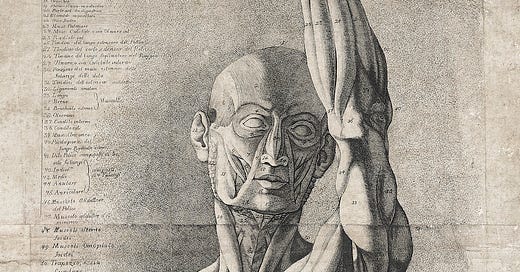

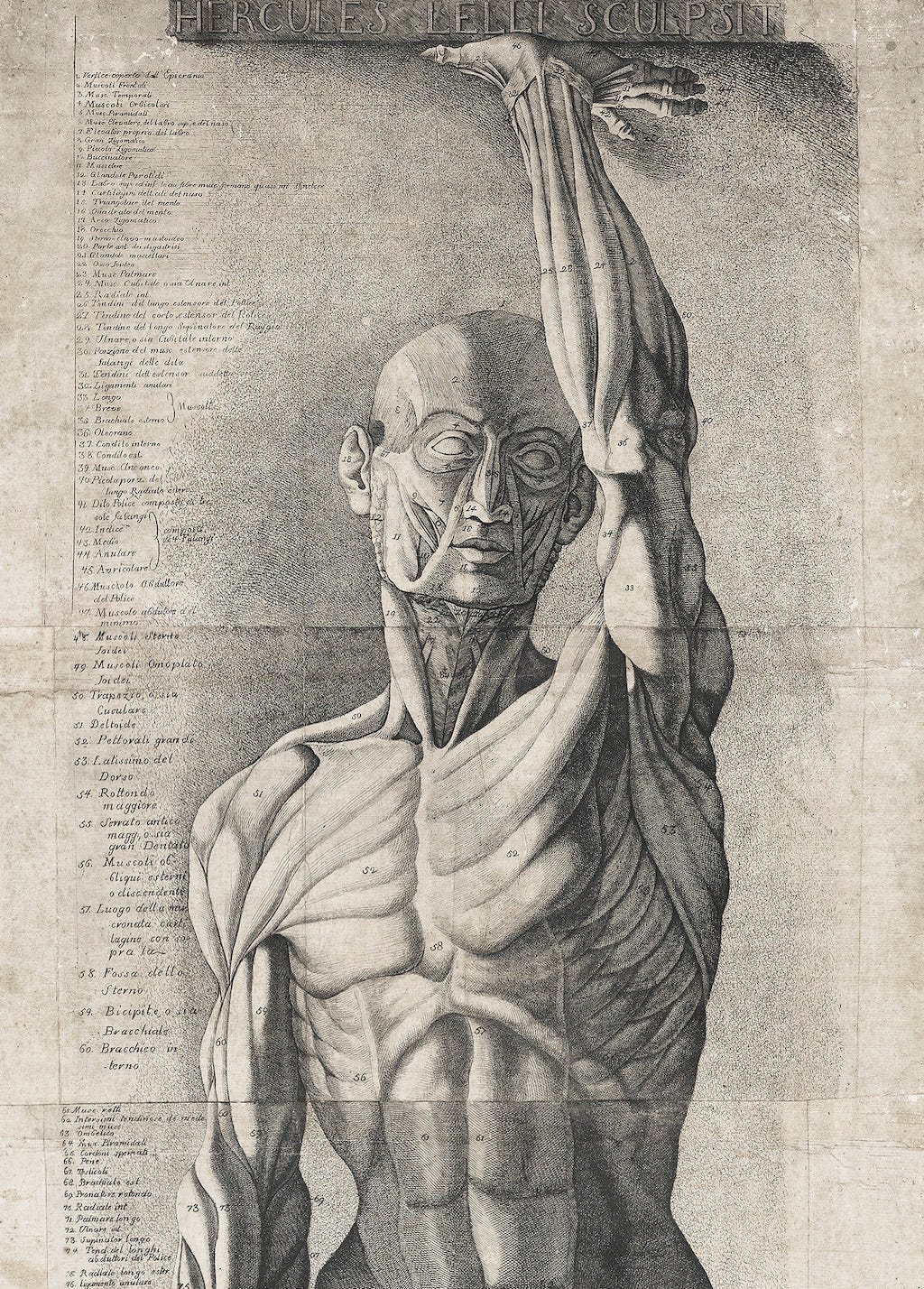

Life-size anatomical figure, Antonio Cattani, 1780

[Merleau-Ponty] talks quite a bit about touch. His thought is that you can, with one hand, touch your other hand. And in that moment, the hand that is touching is, in a sense, using its phenomenal abilities: the ability to touch things and identify what’s being touched. But equally the hand that is being touched experiences itself as just something that’s there to be touched.

—Thomas Baldwin, professor of Philosophy at the University of York

I fight a hook in golf.

It’s an ugly shot that starts straight but screams left—across my face and out of bounds. I can feel it happening even before impact.

Is the problem physical? I’m woefully right-handed, a side effect of a childhood spent throwing baseballs and footballs. Perhaps my right hand is simply pre-programmed to flip, to cast, to turn over: muscle memory gone rogue.

Or maybe it’s mental? A classic case of the yips, my brain tangled in negative thoughts: “Don’t hook it left, don’t hook it left, AH you hooked it left!”

In a sense, it’s both. Just not in the way people usually mean when they say sports are both mental and physical, as if the two phenomena could ever be separate.

“Just remember kids, Football’s 80% mental and 40% physical.”

— Steve Emtman in The Little Giants

No, Steve, it’s actually not like that at all.

Our minds and our bodies are one thing, all of the time. A mindbody.

That’s not a typo.

It’s the subject of today’s quest: to understand our embodiment and do more with it—whether that’s to improve our golf games, manage pain, uncover traumatic patterns, or transform how we connect with each other.

The World of Perception

“The body is our general medium for having a world.” — Maurice Merleau-Ponty

For most people, most of the time, the dominant mode of thinking is basically Cartesian. Descartes famously separated mind from body: there’s physical stuff—planets, houses, rocks, human bodies—and then there’s mental stuff, like thoughts, sensations, and consciousness. According to this view—the view of scientific materialism—we are minds inside bodies: ethereal ghosts operating organic machines.

But is that actually true?

In the early 20th century, a branch of philosophy began to challenge this dualism. It suggested that instead of starting from a detached, scientific vantage point, we begin from within, from lived experience, from how things actually feel as we go about our days.

That tradition is called phenomenology—a mouthful, and a deeply unmarketable name for what might be the most important philosophical movement of the last hundred years. At its core, phenomenology insists that consciousness is always embodied—you don’t just observe the world from a distance; you’re in and of the world.

You are not a mind piloting a body. You are a mindbody.

The tradition began with Edmund Husserl, who wanted to return to “the things themselves,” to peel away layers of abstraction and reconnect with direct experience. Then came Martin Heidegger, who deepened this idea: we are not simply thinking things—we are beings-in-the-world, already and always “thrown” into the world, enmeshed in context, history, and meaning.

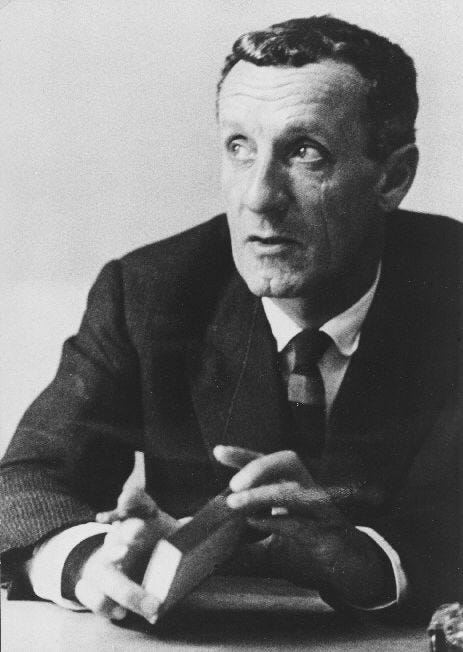

Maurice Merleau-Ponty, a French philosopher of the body, built on this train of thought. His great contribution was to center the physical self not as a meat puppet dragged along by the mind but as the very condition for perception.

Maurice Merleau-Ponty

When you reach out your hand, when you feel cold air, when you navigate a crowd or catch a ball or lean in during a conversation, you are living a kind of intelligence that cannot be reduced to neurons or muscle groups. It is something else: a full-bodied awareness.

The world of perception, or in other words the world which is revealed to us by our senses and in everyday life, seems at first sight to be the one we know best of all. For we need neither to measure nor to calculate in order to gain access to this world and it would seem that we can fathom it simply by opening our eyes and getting on with our lives. Yet this is a delusion. In these lectures, I hope to show that the world of perception is, to a great extent, unknown territory as long as we remain in the practical or utilitarian attitude.

—Maurice Merleau Ponty

This is not just an abstract idea or the idle musings of an armchair philosopher. It’s a profoundly different mode of perception that offers real benefits to anyone willing to jar themselves from their preconceptions.

When you stop treating the mind and body as separate systems—and start understanding yourself as a single, unified sensing being—the world presents differently.

How can we put this epiphany into everyday practice?

Training the Mindbody

Let’s start with sports, where the best athletes already live this way. They speak of rhythm, balance, instinct, and timing. They feel their swing; they know when a shot is good the second it leaves their hand. Their attention is not floating above their body, analyzing, but is rooted inside the movement itself.

Think about the last time you tried to shoot a basketball while overthinking it, stuck in layers of metathought. You break the task into parts: hand placement, knee bend, elbow angle. You try to think your way into the shot. And, inevitably, you miss.

The body doesn’t want a self-conscious coach in its ear. It’s already one thing, a mindbody in the world, and understanding this fact can lead to better performance.

Research backs this up. Studies in golf and other sports show that focusing on external targets—like the flight path of the ball—leads to better performance than obsessing over internal cues like hip rotation or wrist position. Athletes perform better when their body is allowed to act as a single, well-trained system, not when it's micromanaged by a spotlight of thought.

3-D sensory homunculus, showing how our hands and mouths dominate our brain’s sensory map

Which brings us to a different kind of performance: the body in pain.

Dr. John Sarno, the late physician and author, argued that many chronic pain syndromes—especially in the back, neck, and shoulders—aren’t structural at all but the result of repressed emotion, mental stress expressed bodily.

His ideas were and are controversial—you can’t psychoanalyze your way out of structural damage—but nevertheless many of his patients and readers found relief not through surgery but by facing the emotional patterns tied up in their pain.

For years living in New York City, I struggled against what I thought was a bad back: stretching, maneuvering, buying foam pillows and chiropractic gadgets. Then, I read Sarno’s book The Mindbody Prescription and realized that my solutions were in fact part of the problem.

The key point is that the body doesn’t exist in isolation of the mind but is instead always tied up with our mentality and cognitive loops.

The same is true with trauma. In The Body Keeps the Score, psychiatrist Bessel van der Kolk shows how unprocessed trauma imprints itself physically, altering posture, breathing, stress response, and even immune function. Talk therapy alone isn’t enough, he argues. Healing requires somatic experience—movement, touch, and embodied safety. Again, we find the mindbody: not as two non-overlapping magisteria, but one tightly woven system.

I’d also argue that appreciating embodiment is a shortcut to better self care, whether through sleep, diet, or exercise.

Your mindbody probably wants to wake up when the sun rises, as humans have for millenia. It probably wants to eat food that satisfies your whole being, not just a habituated craving or a number on a nutrition label. It probably wants to move frequently across physical horizons, as it evolved to do.

This is partially why fast and processed foods are so addictive: they satisfy the mindbody in repeatable, engineered ways. It’s also why some consumer products are so satisfying: the iPhone, a beautifully worn leather bag, a great pair of running shoes. They feel right because they’re designed to harmonize with how we move, touch, and interact. They’re tuned to us.

Finally, there’s the social dimension.

Seeing others as mindbodies themselves—not just as disembodied talking heads—can change how you work. The best leaders, negotiators, and salespeople are physically attuned and pick up on subtle cues. They sense tension before it’s voiced. They notice when someone’s posture shifts in a pitch meeting, when a potential partner’s voice tightens during contract terms, or when a colleague avoids eye contact after a decision.

This is body literacy, and it can create real advantages, a palpable, measurable edge: better retention, faster deals, fewer conflicts, more cohesion. The signals and effects are subtle, but the benefits are very real.

Whatever entry point you pursue—personal, professional, philosophical—training yourself as a mindbody offers a way to operate in the world with more clarity and self-assuredness.

It’s truer to who and what you are.

So with that…

Here’s Quest 25:

Train Your Mindbody

Key Details:

Change the way you move: notice how and when your body tightens, your posture stiffens, your breath shallows. Break up habituated patterns.

Interrogate your pain: whether it’s a physical ache or a mental block, treat everything as a signal—not something to be ignored but a message to be decoded.

Apply mindbody thinking at work: in your next meeting or negotiation, read the room like a full-body text. Pick up on cues, and, to use a worn cliche, be present. It makes a difference.

As always, thanks for reading!