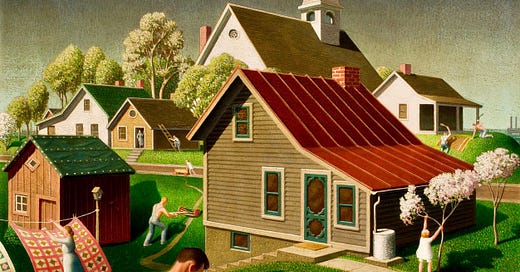

Grant Wood, Spring in Town, 1941

Greetings, traveler!

Welcome to the world of Quests, where we focus on purpose-driven people and the ideas that animate them.

Leave your troubles behind, and follow me into the town square.

Today we're meeting Charles "Chuck" Marohn, a writer, municipal engineer, and urban planner from Brainerd, Minnesota.

Chuck Marohn is obsessed with towns and how they're built—now and long ago. He argues that post-WWII suburban expansion and car-centric infrastructure have trapped Americans in a self-defeating development pattern. We build cities that make people unhappy, towns that bleed money, and "neighborhoods" that ignore how humans have lived for thousands of years.

Marohn favors slow progress over quick fixes, incremental development over splashy projects, and fiscal and moral responsibility in urban planning.

To liberals, Marohn sounds like a conservative; to conservatives, he sounds like a liberal. Jane Jacobs is a personal hero to Marohn; so is the Czech economist Tomas Sedlacek, who has argued against the fetishization of growth.

If Marohn's ideas resonate with you, take on your first Quest. Rewards await.

In the meantime, grab your gear. Let's go for a walk.

STROADS TO NOWHERE

Back in 2011, Chuck Marohn coined an ugly word for an ugly thing: stroads.

Part street (where people walk and shop), part road (where people drive), these 20th Century abominations try—and often fail—to do two jobs at once as they connect us to our Olive Gardens and our Best Buys. Community life becomes an afterthought in the face of drive-up, hustle-in, get-out consumerism.

No one likes a stroad, but they’ve come to feel like a necessary evil given our dependence on cars and our preference for big-box, big-footprint retailers.

Marohn compares stroads to a futon—neither a good bed nor a good couch. Just as a futon doesn't excel at being either piece of furniture, a stroad isn't as effective as a street or a road.

Instead, they’re an unsightly reflection of how the automobile transformed not only the physical landscape of the United States but also our mental architecture and daily experiences. We’ve created a world of strip malls, parking lots, stroads, and other “non-places.”

A DIFFERENT VISION

For Marohn, stroads are emblematic of a bigger problem: the funneling of public dollars into “infrastructure” under the banner of growth and job creation, often without considering long-term consequences. Tax incentives and subsidies tempt local governments into approving costly projects they believe will boost the economy. In reality, these projects strain public resources and infrastructure.

“When we build a road or a bridge or a mile of pipe, we’re left with an eternal maintenance obligation. If the project costs more than the wealth it creates – which most of the projects we are undertaking today do – then we’re just getting poorer, regardless of job creation” (from Strong Towns, p. 73).

Marohn isn't saying that all (st)roads are bad—but they don't all lead to Rome either. The same goes for sprawling subdivisions and massive sports stadiums. Many of these grand projects saddle communities with long-term financial obligations that outweigh their benefits.

Instead, we should do the kind of math that any enterprising high schooler could do—balancing liabilities and assets. By simply comparing the cost (liabilities) to the items of value (assets), it's often clear that these developments don't make fiscal sense.

(Sidenote: Roads, in Marohn’s view, aren’t assets: “Any rationally minded person understands that the street in front of your home is not an asset for the community. It can’t be picked up and sold to the neighboring town. It can’t be pledged as collateral against a debt. The street is a liability, plain and simple.”)

Projects like multi-lane roads require ongoing maintenance, policing, and infrastructure support, which can strain municipal budgets. Take Lafayette, Louisiana for example, which “grew its liabilities thousands of times over in service of a theory of national growth, yet its families are poorer” ( from Strong Towns, p. 101).

“If you’re frustrated that your community can get $58 million for an overpass on the edge of town, but can’t seem to get a simple crosswalk painted, you’re not alone” (source).

So what's the alternative?

Marohn envisions a return to slower, denser towns and cities that prioritize walkability and organic development. He advocates for communities designed on a human scale, where streets are safe and inviting for pedestrians, and local businesses can thrive without being overshadowed by massive retail chains.

There's a romantic flair to his vision and a clear-eyed, Midwestern practicality. He harkens back to ancient cities like Pompeii, which evolved over time to meet human needs rather than being built all at once.

SPOOKY WISDOM

Marohn calls this unspoken understanding of how towns naturally grow "spooky wisdom"—the accumulated knowledge that communities develop over generations without even realizing it.

Spooky wisdom is embodied in pre-modern development: the way human beings organize around town squares and water sources; the allowance for “small bets” and failures and gradual progress; the expansion of towns in accordance with the practical needs of locals rather than the monetary desires of those far afield.

“When city regulations demand that everything be built at a large scale and to a finished state, we not only price out much of society but we ensure that many of those who do own a home will struggle with that investment” (from Strong Towns, p. 163).

Marohn believes that traditional ways of building towns carry this innate “spooky” wisdom. Instead of imposing grand plans or flashy projects, local governments should trust the time-tested patterns that empower everyday citizens. Big projects aren’t inherently bad, but subtler solutions might present themselves if you’re paying attention.

PUBLIC VS. PRIVATE INVESTMENT

In part, spooky wisdom means that private investment should lead public investment. When individuals and local businesses invest in their communities, it reflects genuine needs and sustainable growth patterns.

Public funds should be used strategically to support these grassroots developments rather than chasing after large-scale projects that may not serve the community's best interests.

Public Investment Leading Private Investment from Strong Towns: A Bottom-Up Revolution to Rebuild American Prosperity (p. 33) by Charles Marohn

Private Investment Leading Public Investment from Strong Towns: A Bottom-Up Revolution to Rebuild American Prosperity (p. 31) by Charles Marohn

Marohn’s is a bottom-up philosophy that values free enterprise and local wisdom while still recognizing the government's role in facilitating positive change.

A BALANCING ACT

Marohn’s greatest strength as a communicator and activist is that he isn’t overly concerned with political parties or tired debates, like NIMBY vs YIMBY or degrowth vs pro-growth vs smart growth.

If you tried to label Marohn, he’d fit into an odd-shaped box: a Gen Xer with the fiscal mind of a libertarian, the moral makeup of a small c conservative, and the bleeding heart of a liberal.

Not everyone agrees with Marohn. Critics of Strong Towns agree that while incremental change is valuable, it isn’t enough to tackle larger issues like affordable housing or inadequate public transportation. Big changes require big spending. Marohn addresses such critiques here.

Regardless of one’s views on urban planning and government spending, we all know and feel that something has gone wrong in the way many of our towns present themselves to us, in the allocation of public and private dollars, in the dreariness of dollar store parking lots and deteriorating strip malls. We know we can do better.

SO WHAT SHOULD WE DO?

For one thing, Americans should think very carefully—not dismissively nor on blind faith—about government regulation. Rules matter. The details really matter. Read your local newspaper, and pay attention to your town hall’s agenda.

As for what you can do today—right now—here's what Marohn suggests:

Humbly observe where people in the community struggle.

Ask: What's the next smallest thing we can do right now to address that struggle?

Do that thing. Do it right now.

Repeat.

As he puts it, “We don’t form a committee. We don’t hire a consultant. We don’t pause eighteen months while our grant application is processed. We’ve humbly identified a struggle and then identified the next smallest thing we can do about it, so we just go out and do that thing” (source).

If a crosswalk needs better visibility, then advocate for clearer markings or signage. If a vacant lot needs a purpose, then propose starting a community garden. If local businesses are struggling, then organize a "shop local" campaign.

In short, open your eyes to the world around you. Interact with it.

At Quests, we’ll support you if you do.

HERE'S QUEST 1:

Do the "smallest thing" you can to improve your town.

Maybe it's picking up litter on your street, helping a neighbor with their yard work, or organizing a block party. No action is too small.

Quest Tips:

Use social media to identify opportunities. Follow your town’s social media account(s); join your town’s subreddit (if applicable), Facebook, or Nextdoor group.

Check your town/city hall’s website for past/upcoming meeting agendas. Copy and paste the details into your favorite LLM (like Chat GPT) and get a summary of what’s happening in your town. Find a niche where you can help.

Walk. That’s it, that’s the tip. Walk a lot, and talk to people. You’ll find something that needs done.

I’ll highlight the most creative and impactful adventurers with a future write-up about their daring exploits!

Please comment here on Substack with thoughts, counterthoughts, suggestions, and disagreements.

To tumble further down the rabbit hole, head over to the Quests Community.

Upon completion:

It’s dangerous to go alone—find a quest partner, and party up.

Recommended Reading:

Strong Towns: A Bottom-Up Revolution to Rebuild American Prospersity (Charles Marohn)

A Better Brainerd (examples of incremental projects that everyday people can do to improve their towns)

The Death and Life of Great American Cities (Jane Jacobs)

Contra Strong Towns (this is an even-handed critique of Strong Towns; he makes good points, but I’d argue that Marohn is still pushing conversations—and actions—in the right direction)

NEXT ON QUESTS

Next week we'll move on from the spooky wisdom of days past and gaze into the future as we explore the intriguing world of superforecasters and the timeless allure of a question that's captivated humanity for centuries: Can the future be known? We'll delve into how modern-day oracles—investors, gamblers, and data enthusiasts—seek to forecast the unknown, turning insights into opportunities to make their fortunes.

In the meantime, quest on.

I started a campaign in my city to amend legislation to allow hens. We are getting SO much push back.

I bring my family on walks, city cleanups, I organized a planter contest to beautify our main drag. It seems like instead of getting on board, many complain.

If you ask me, one of the biggest issues all cities face are zoning laws. No one wants to live next door to a gas station, but small, walkable economies that allow bakeries, shops, and family owned diners in largely residential areas would do so much for the walkability and the "destination". So much of our cities and towns are taken up by parking lots and gas stations, oil change services, and banks. There is so little to actually do and do few people to go out and meet.

To top that off, the "hustle culture" leaves so little of our time to "us" that it's hard to take advantage of small local businesses because their open hours conflict with normal working hours. It's a lose lose. This is something that makes me feel doomed more frequently than it has a right to.