from Whiplash

Welcome back to Quests, where we clarify, gamify, and—in this week’s newsletter—Spotify our way to a better future.

Today we’re roaming the Arts District where musicians, writers, and poets gather to charm the masses.

Troubadour, a scrappy quartet, is playing the local tavern. They’re an up-and-coming (and, yes, entirely fictional) rock n’ roll band within our miniature world of Quests.

Their songs are great. They’ve racked up 100,000 streams on Spotify this year. Their reward?

$280.

That’s…not much. The average payout on Spotify is ~$0.004 per stream.

But before we bemoan the rise of poor-paying streaming services—and there’s plenty to critique—let’s rewind a bit and understand how we got here.

A little more than a decade ago, the music industry was grappling with a full-blown crisis: CDs and digital downloads were fading, piracy was rampant, and revenue streams were drying up.

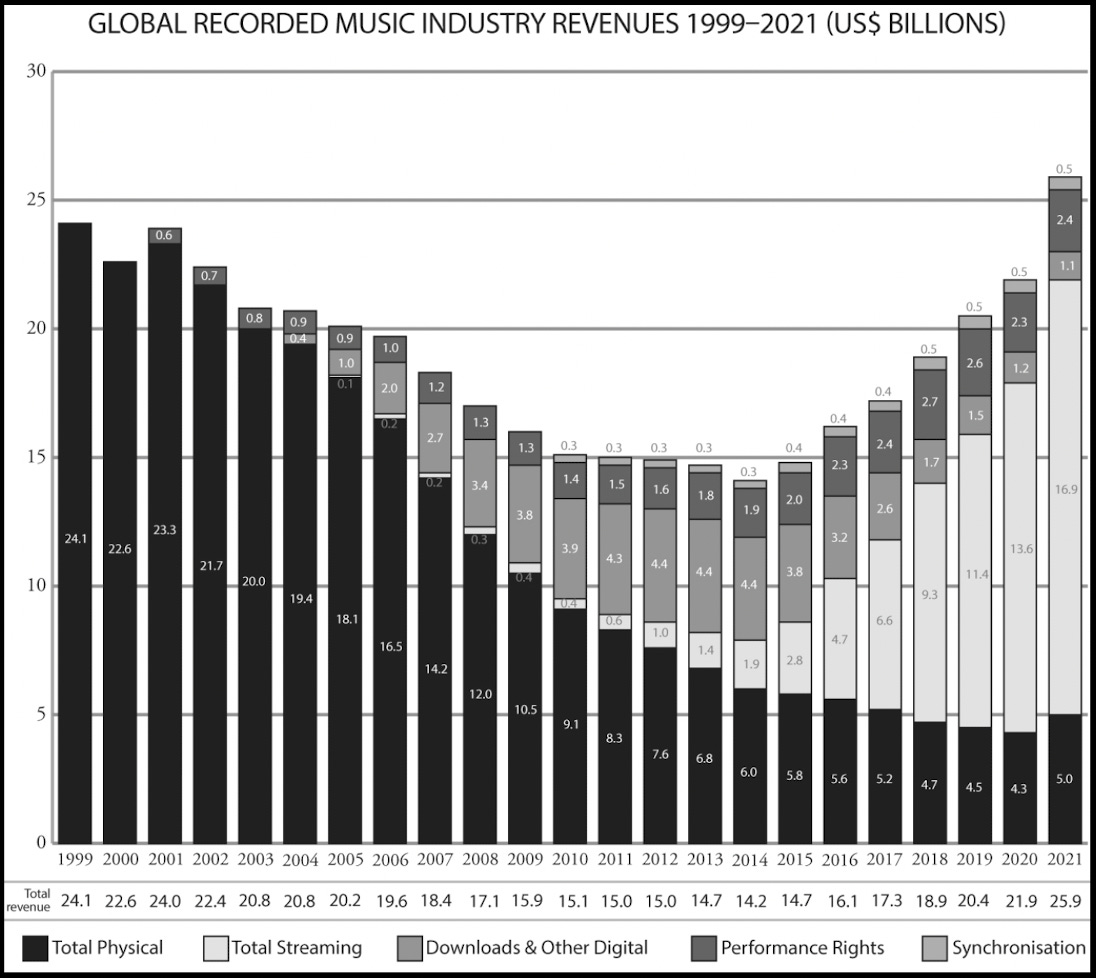

2014 was the bottom. Chart from How to Make it In the New Music Business.

Then streaming emerged, first as a lifeline and later as the dominant model. Spotify saved music—or doomed it, depending on whom you ask—forever altering not just how we listen to songs but also how they’re made (more on this soon).

Pay $12/month, and you get the keys to all of music-dom. That’s insanely favorable to us as consumers.

Meanwhile, new artists like Troubadour are left to navigate a shifting (and mostly non-physical) music landscape.

Let’s map that territory, get to know the players, and understand how we as listeners can help lesser known artists.

Lute up. Turn your amps to 11. This post should be played loud.

From Solid Records to Clouds and Streams

It’s easy to forget how radical the jump was from music being a physical industry to one that’s almost entirely digital.

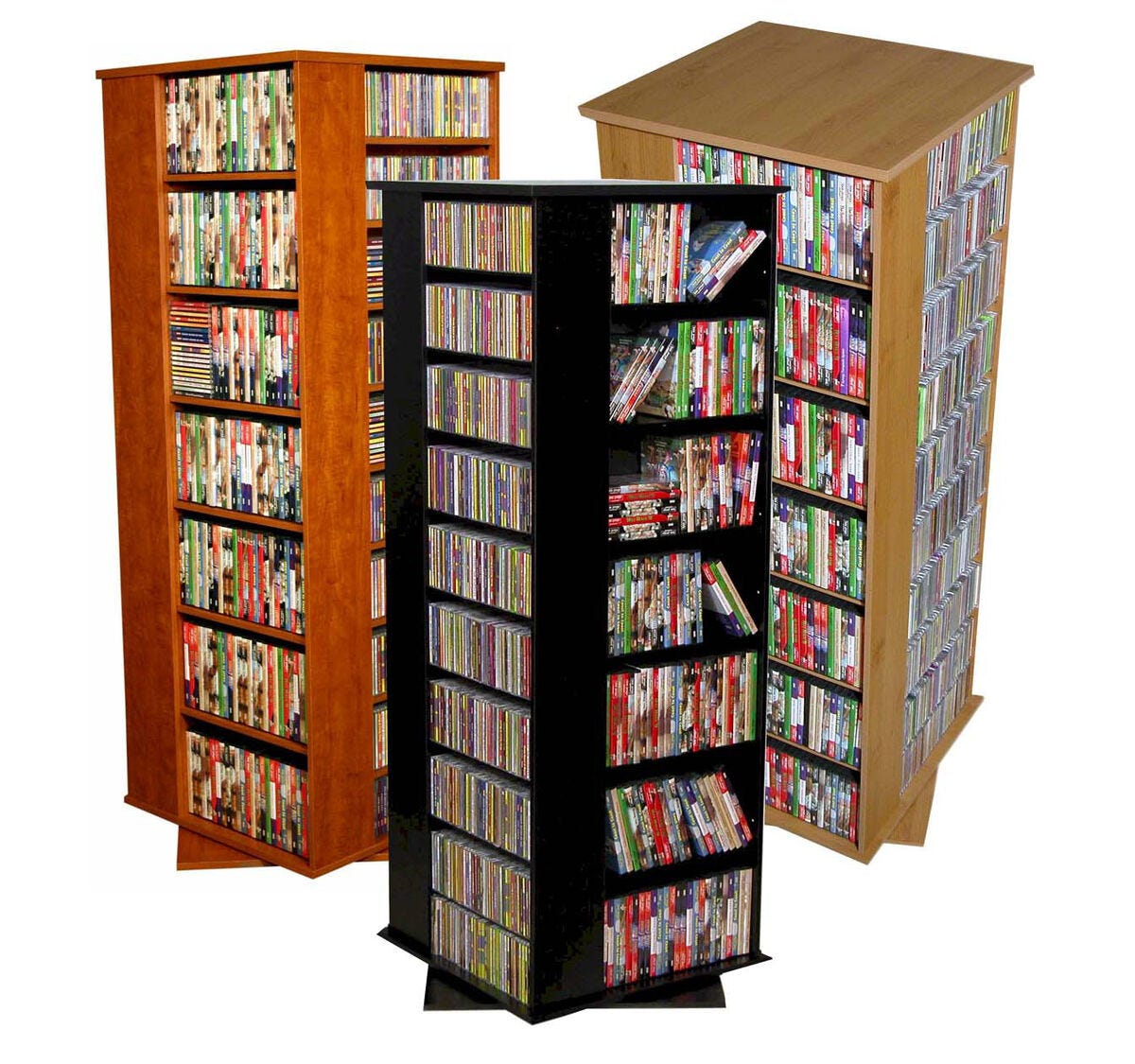

Record companies were called “labels” because of the literal stickers on vinyl records, back when people shopped in actual stores for music. When I was a kid, in the halcyon days of the late ‘90s and early 2000s, people had “media rooms” (remember those?) stuffed to the ceiling with games, DVDs, and CDs.

‘Member?

There was still a basic coherence to the culture. Music felt solid, visible on MTV and divisible into discrete genres that were represented on real shelves. You knew where to find the country crooners, the “alternative” rock bands, the hip hop aisle.

Obviously, that’s all changed. No one needs (and few even want) physical copies of anything, and, as music has moved to the cloud, the traditional genres have dissolved into a blur of mashups and hybrid sounds. In the age of playlists and vibes, genre feels almost quaint.

Spotify saw this shift coming and accelerated it. When they launched, the music industry was stuck between two eras—an awkward interim when everyone bought individual tracks on iTunes for 99 cents a song…or just torrented entire artist discographies. If Troubadour, our house band here at Quests, had existed in the ’90s, they’d be chasing a record deal, hoping for CD sales (with an emphasis on sales: remember “ripped” CDs?), maybe even getting a bit of radio play if they were lucky.

Daniel Ek, the founder of Spotify, realized he could make piracy irrelevant by offering a product that was somehow even better than free. He just needed to win over a handful of industry giants to unlock vast music libraries for anyone willing to pay a modest subscription fee. The major labels—Sony, Universal, Warner—held the keys to the catalogs that would make Spotify a go-to platform.

Daniel Ek. Image.

How could Spotify afford this? Ek convinced labels that they could either resist change and risk losing out, or embrace it and enjoy new sources of revenue. And he started with significant financial backing, securing around $20 million in initial funding.

Ek promised the labels revenue from millions of users and even offered equity stakes in Spotify itself. Ek understood they would burn through cash (and they did), but he banked on one key idea: if Spotify became the platform for on-demand music, it would establish itself as the epicenter of the music universe.

For listeners, Spotify’s offer was simply too good to refuse.

I know that whenever I review my monthly subscriptions, Spotify is never on the chopping block. In his mission to revolutionize music playback, Ek receives a “Quest Completed” checkmark to the tune of six billion dollars in net worth.

Obviously great for Spotify and for consumers. What about music artists?

Surviving the Stream

First keep in mind that there are many players in the music industry who all want their slice of the pie. Unless a band like Troubadour goes fully DIY—cutting out the middlemen, which is feasible today but fraught with its own risks—they’ll end up sharing revenue with their record label, publishers, distributors, and platforms like Spotify.

It’s important to hold in mind the sheer complexity of the situation facing young artists.

On the business side, figures like Lucian Grainge, the head of Universal Music Group, have “helped record labels rake in billions of dollars from streaming.” (Check out John Seabrook’s profile of Grainge in the New Yorker; it’s fantastic).

Grainge and the other label heads act like venture capitalists: they invest in new acts, providing capital and taking on risk, hoping to make an outsized return on one or two big winners. And while that role is essential, with labels funneling millions into artist development and marketing, everyone can’t be a winner.

There’s nearly $30 billion to go around annually in the music industry—a decent number until you compare it to movies (~$100 billion) and gaming (approaching $200+ billion). With too many aspiring musicians, too many people taking their cut, and too little revenue to go around, artists are left with scraps unless they’re achieving tens of millions of streams.

For all its flaws, streaming is the new reality and will be for some time. Revenues continue to climb. So why can’t Spotify pay artists more?

(Sidenote: as Ek often reminds his critics, Spotify doesn’t always pay artists directly—they pay the labels.)

Distinctions aside, why isn’t the per-stream rate higher than $0.004? Why not closer to $0.006, or even approaching demands from groups like the Union of Musicians and Allied Workers, who advocate that Spotify pay artists at least a penny per stream?

Well, because Spotify’s entire business model is built on volume. To pay significantly more per stream would require a radical overhaul—either with price hikes for users, a drastic reduction of free-tier listeners (who make up a large chunk of the platform’s user base), or somehow persuading record labels to take a smaller cut (good luck with that). And since the major labels hold a controlling stake in Spotify’s payout system, the odds of such changes happening anytime soon are slim.

It’s a delicate system, and Spotify is caught between keeping artists, listeners, and label executives happy—often a losing game.

But music artists must play along.

Ari Herstand, author of How to Make It in the New Music Business, writes (with echoes of Annie Hall), “Withholding music from streaming because it doesn’t earn as much as downloads is like a farmer refusing to sell eggs because they don’t earn as much as the chicken. Sure, it may not make as much money today, but it will tomorrow. And the fact of the matter is, people want eggs, they don’t want chickens.”

So what should artists do to actually make money?

Herstand continues: “You have to find ways to monetize your fan base—outside of simply getting them to stream (or buy) your music. Streaming is the loss-leader for future sales opportunities. The foot in the door.”

To drive revenue from concerts and merch and sponsorships, streaming must be embraced (even begrudgingly), and artists should do everything in their power to boost streams (short of stream farming) and get featured on playlists, especially editorial playlists where songs have the potential to go massively viral.

Of course, some artists have taken this chase for streams too far: shortening songs, front-loading choruses to hit before the 30-second mark (which counts as a stream), or breaking songs into multiple parts to inflate their numbers.

It’s a stream

Good art shouldn’t be compromised to appease algorithms. But music artists should know that the stream is the path to discoverability; once found, you can climb out and up.

And music fans need to realize that now, more than ever, it’s crucial to support the artists they love and help nudge the algorithm in their favor.

Lifting Up Music Artists

Alright, so you’ve fallen in love with a band like Troubadour—I picture them as dwarven warriors, but use whatever example/image you like—and you want to support them.

What should you do?

In short, you need to stan efficiently. Here’s a quick rundown:

Go to Shows. Buy Stuff.

Artists make more $$ when you buy merchandise directly at shows or from their website.

Stream, Stream, Stream

Listen to your favorite artists often—and maybe even on low volume while you sleep (muted streams don’t count). I’ve been streaming Brave Baby, a band local to my new hometown of Charleston, SC, as often as possible.

DM Artists

Thanks to Spotify’s algo, I discovered Kensuke Sudo, a twenty-year old Japanese rock artist from Osaka who sounds eerily like The Beatles. I messaged him on Twitter, and he told me he’s hoping to tour the U.S. next year. I wouldn’t have known if I didn’t reach out.

Share Your Enthusiasm

I’ve probably messaged more than a dozen friends about the band Geese from New York, who released an incredible album last year, 3D Country. Ask me about this band; I will annoy the sh*t out of you singing their praises.

Finally, I’d love to see Spotify add a DONATE button and more community features to connect listeners directly with artists. Labels might not love it, but it would create a better experience for musicians and their fans—and that should be the priority. I understand how difficult it is for Spotify to budge on royalties, but they can do a better job of empowering artists to interact with fans and succeed off-platform as well.

Troubadour—yes, I’m committed to this imaginary band of Gimlis—have finished their final encore. Now it’s closing time in the Arts District, and you need to do your part.

Here’s Quest 5:

Share a favorite lesser-known music artist

Key Details

Comment below, or, better yet, post on the Community page to earn rewards

Write a brief description, link to a playlist, share a concert photo: however you want to highlight an artist or band.

I’ll create a playlist compiling all the contributed comments/entries—should make for some interesting listening! Please resist the urge to include meme songs, such as Rick Rolls, Booty Man, and Jesus Is My Friend. I do encourage everyone to listen to these songs, though.

Please comment here on Substack with thoughts, counterthoughts, suggestions, and disagreements.

To tumble further down the rabbit hole, head over to the Quests Community.

Upon completion:

It’s dangerous to go alone—find a quest partner, and party up.

Recommended Reading:

All You Need to Know About the Music Business

How To Make It In the New Music Business

The Song Machine: Inside the Hit Factory

NEXT ON QUESTS

Ready to save some money? We’re heading to the Bank, where we’ll explore the world of private equity and the leading firms’ always rigorous, sometimes cutthroat cost-cutting techniques.

What lessons can we glean and apply in our own personal lives?

Prepare to Marie Kondo your finances.

In the meantime, quest on!

So strange that artists and bands don’t make the bulk of their earnings on their actual art; the music. I’ve always been told that the best way to support an artist is to purchase their musically directly rather than stream, but that can seem inconvenient when platforms like Spotify and Apple music reign supreme. Hopefully a new way to easily support your favorite artists will become popular in the near future.

Small artist I’ve been enjoying lately: Kyle Emerson (in particular, his song Are You Lonely). He’s based in Denver, and is super talented.

So interesting to think about how the advent of streaming platforms has affected genre. With the way music has evolved in terms of consumerism and actual sound, it's become difficult to categorize some artists within the traditional bounds of genre.

A small artist i've been listening to recently is Florence Adooni, an afro-soul artist. I've been trying to expand my listening to more international artists and I've been loving her music!