I’m not a birdwatcher, but I enjoy watching birds—especially the family of ducks that live across the street. Their names include Brownie Batter (she’s brown), Andrew Jackson (he’s mean), and Mr. Pickles (he’s…greenish).

I’ll sit on the porch and watch as they bob for plants to eat, preen each other’s feathers, and waddle into the exact middle of the street.

What fascinates me about ducks—and animals in general—is how arbitrary their actions can seem.

Why does Brownie Batter take three steps this way instead of that way?

Why does Andrew Jackson snap at the others?

Why does Mr. Pickles huddle under that tree in particular?

Looking into the brown and black of their vigilant eyes, I’m led into a very old question and the topic of today’s quest: “Is anyone in there?”

Animal Minds through Time

For a long time, the answer was no. Aristotle held that animals are without reason, without language, driven purely by instinct.

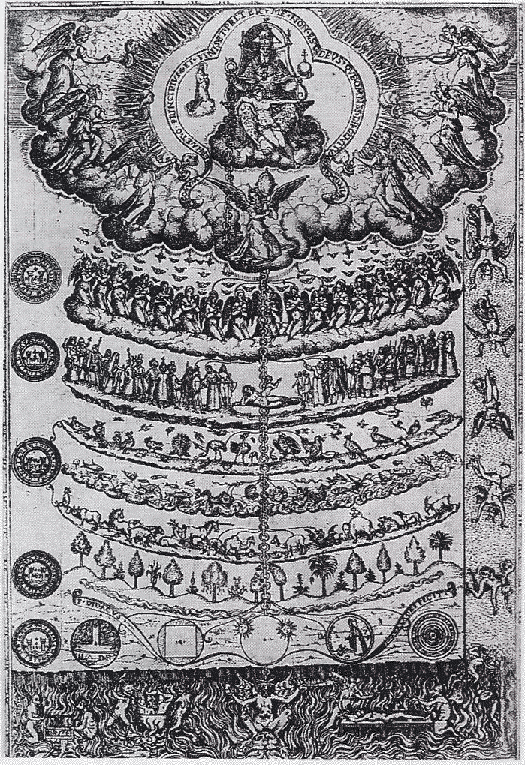

Within the Great Chain of Being, animals ranked above plants and minerals but below humans, who alone possessed access to the divine through the light of the rational soul. Animals move; they sense. But they do not know and cannot reason.

The Great Chain of Being

This view remains implicit in much of our thinking today, though few would put it so bluntly. For Medieval and Renaissance thinkers, viewing animals as soulless automata followed logically from a theological framework in which God governed all outcomes and left no room for independent consciousness outside the human soul.

Descartes was explicit about the non-existence of souls in animals, often comparing them to clocks and machines. (There are also stories, maybe apocryphal, about Descartes kicking and dissecting dogs.) In any case, a stable hierarchy persisted for many centuries, with humans and animals existing on different planes.

This neat picture would be challenged in the modern age. More than a hundred years before Darwin, David Hume suggested that “no truth appears to be more evident, than that beast are endowed with thought and reason as well as men.”

This would become a common-sense view, steeped in empathetic experience, and Darwin himself subscribed to the idea that animals possess minds something like our own. In The Descent of Man, Darwin writes, “The difference in mind between man and the higher animals, great as it is, certainly is one of degree and not of kind.”

Darwin’s final book, The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals, is dedicated to the subject of mental states and what sorts of continuities persist between species. Humans are but one “form” among many in a chain that stretches back billions of years; as Darwin famously wrote: “Endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.”

Somewhere along the way, consciousness emerged. And with every new observation of intelligent behavior in apes, dolphins, octopuses, fish, crows, and even insects, there’s ever more reason to agree that the mind is not the privileged property of a single species.

After Darwin

And yet uncertainty prevails. Despite the apparent journey from species divided to species continuous— and despite the impressive displays of memory, problem-solving, and perhaps even sense of self among various species— many ethologists still hesitate to speak definitively on the question of animal minds.

Consciousness, of course, is an immense question-mark even before animals enter the picture. This is David Chalmers’ Hard Problem: how is it that a series of neurochemical interactions—intricately complex but ultimately physical in essence—give rise to mental experience, to the peculiar sensation of peering out at the world from behind a pair of eyeballs?

In even simpler terms: how does physical stuff produce non-physical being, i.e., conscious experience?

This is the big mystery, and it has significant implications for scientists who study animal behavior. We are deeply confused about our own minds; how can we know about the minds of other people, let alone other species? Frans de Waal, a primatologist and author of Are We Smart Enough to Know How Smart Animals Are?, represents this position in an interview when asked, “Would you say that animals other than humans have consciousness?”

De Waal responds:

I don’t know what consciousness is. I know that I’m conscious, but I’m not even sure that you’re conscious. You can tell me that you are, but I might not be convinced – it’s a subjective experience. But you might think that there are certain things – metacognition, planning, having specific memories of the past – that are impossible without consciousness. So, for example, apes and one parrot have passed the marshmallow test that psychologists give to children – so they can delay instant gratification for the prospect of a larger future reward. You might say that it’s unlikely that apes and parrots are doing without consciousness the same thing we are doing with consciousness.

Frans De Waal is hesitant. He’s hesitant, in part, because of the still-powerful influence of twentieth century behaviorism, which insisted on verifiability in the objective, shared world. In his book, De Waal underlines some of the criticisms that he’s faced over the years: “I can’t count the number of times I have been called naïve, romantic, soft, unscientific, anthropomorphic, anecdotal, or just a sloppy thinker for proposing that primates follow political strategies, reconcile after fights, empathize with others, or understand the social world around them.” He and others (including Donald Griffin, Sara Shettleworth, and Hans Kummer) have fought long and hard in making the case for animal cognition. Consciousness, however, as something distinct from cognition, remains another story.

Here is De Waal once more, reflecting on the 2012 Cambridge Declaration of Consciousness: “…I was skeptical. The media described it as asserting once and for all that nonhuman animals are conscious beings. Like most scientists studying animal behavior, I really don’t know what to say to this. Given how ill-defined consciousness is, it is not something we can affirm by majority vote or by people saying ‘Of course, they are conscious—I can see it in their eyes.’ Subjective feelings won’t get us there. Science goes by hard evidence.”

This brings us back to my core curiosity about what lies behind animal eyes: is there an “I” on the other side? It seems the lights are on, but is anyone home? Is there, as in Thomas Nagel’s famous formulation, something that it feels like to be an ape, a dog, a bat, a fish, an insect?

When considering other people—and putting aside flights of radical skepticism and talk of philosophical zombies— the answer is almost always yes, someone is home: daily life would look very different if we didn’t adhere to that base assumption. For animals, however, there seem to be many answers, depending on how one defines terms like “consciousness” and “mind,” what particular species is in question, what the animal is doing at a given moment, and how much significance one ascribes to brain structure and neuron count (always a lot, but how much?). Is there a magic number of neurons, firing in just-right configurations, that gives rise to the feeling of being?

In the end, answering the question of animal minds can feel like guesswork. We want to say that dogs certainly have minds and that oysters certainly do not, but we struggle in the majority of animal cases, which of course has major ethical implications, as Peter Singer and others have rightly pointed out.

Much of it has to do with the matter of expressiveness, specifically expressiveness as crudely measured in the eyes of animals.

Animal Eyes

We human beings are obsessed with eyes. Eyes symbolize the light of consciousness, the inner light of being. You know all the cliches. That eyes are the window to the soul. That eyes speak louder than words.

Do these cliches hold true for wordless creatures? What might the eyes of animals tell us about their interiority, if anything?

A few years ago John Jeremiah Sullivan wrote a piece for Lapham’s Quarterly on the subject of animal consciousness in which he emphasized an eye-struck moment: “I go back to our first family dog […] I can still hear people, guests and relatives, talking about how smart she was. ‘Smarter than some people I know!’ But when you looked into her eyes—mahogany discs set back in the grizzled black of her face—what was there? I remember the question forming in my mind: can she think?”

The eye-to-eye moment is the point of departure. The debates about which behaviors indicate how much intelligence, whether intelligence can exist independently of consciousness, how one can possibly make moral determinations in the absence of what Nick Lane calls a “consciousometer”–all of these properly scientific and philosophical questions come after the original face-to-face encounter. And I suspect our minds are made up fairly quickly based on what we see there.

Douglas Hofstadter describes his own encounter with a dead pig in I Am A Strange Loop, a freewheeling exploration of consciousness from his materialist point of view. For Hofstadter, consciousness “is an outcome of physical law.” Consciousness is “a pattern” which “reaches full bloom when there comes to be a deeply entrenched self-representation—a story told by the entity to itself—in which the entity’s ‘I’ plays the starring role, as a unitary causal agent driven by a set of desires.” In other words, consciousness is a remarkable outcome of certain physical relationships that can arise in the physical world.

Before he spells out this conclusion, however, Hofstadter provides what he calls a “consciousness-cone,” a representation of how much “soul-ness” various natural entities possess.

This is a thought-provoking representation. Another materialist philosopher like Daniel Dennett (with whom Hofstadter wrote a book) might downplay it as folk psychology, but there’s a usefulness in considering everyday conceptions of animal minds. It can tell us something about our way of looking when we peer into the eyes of other beings.

Notice the location of dogs, right below humans and followed by bunnies, chickens, and goldfish. Based on what’s observable, I think most people would agree that dogs are more intelligent than bunnies, chickens, and goldfish. But more conscious? How could we possibly discern the differences between the inner life of a mammal, bird, or fish? Of course, we live out the notion that there are discerned differences all the time. Pet dogs are buried, and pet fish are flushed.

Notice, also, that we’re predisposed to acknowledge that mammals, birds, and fish possess some form of inner life while—in the case of the bee, mosquito, and mite—we ascribe “Little or no consciousness.” Bugs are squashed without a second thought.

The divisions here between dogs and fish and fish and insects are significant. I’d argue that Hofstadter’s consciousness-cone neatly captures an important aspect of how we instinctively ascribe mind and rank the animals: we privilege faces like our own, particularly mammalian faces with expressive eyes.

Dogs, in particular, win above the rest because our two species have co-evolved. Dogs have learned to look back at us: they maintain eye contact, follow our gestures, and even manipulate us with their eyes if some studies are to be believed. It’s been demonstrated that dogs and humans both experience the release of oxytocin, the “love chemical,” when gazing into the other species’ eyes.

Other mammals, too, seem to speak to us through their eyes. The eyes of pigs look uncannily like those of humans, and, if you’ve ever seen the horrific footage from within the slaughterhouses, then you know that pigs and cows appear to be in a state of pure terror when they’re next in line. It’s written on their faces, as people say. Do they know what’s about to happen, or do they simply look as if they know? How could they “know” without minds?

Fish eyes are similar enough to those of mammals, though many species have evolved remarkable adaptations. Nevertheless, fish, I’d venture to say, do not convey to us in emotional exchange as mammals seem to do. It was long thought that fish do not feel pain, but new research suggests otherwise. I can’t help but think of the fish tank at the sushi restaurant and wonder if children would still tap, tap, tap the glass if the fish had different faces.

Still, fish rank well above the soulless insects, which exist in such remarkable quantities that if they did have thoughts and feelings, then every day would be something of a tragedy with so many smushed minds on windshields. Surely there must be some level of representative feedback between the insect and the world, so that it can successfully respond to outside stimuli. Bumblebees learn, and cockroaches remember. Still, the tendency here is to suggest, as Hofstadter does, that there is some small kernel of consciousness in insects (a Darwinian difference in degree, rather than kind), but it is so minuscule as to be morally irrelevant.

That seems fair enough for most people. And yet I still sense a large divide between the tiny gnat (we call them “noseeums” in South Carolina), with its minuscule compound eyes that I can’t possibly see, and the praying mantis (mantis coming from the Greek word for “prophet”), an insect with a face and arms and legs and— I want to say—a mind.

In the end, appearances matter when thinking about the relationship between animal eyes and animal “I’s”. We bring our own psyches to the table, so that our looking on animals is always charged with emotion, language, imagery, etc.: the full suite of human consciousness and all it entails. This phenomenon might be described under the catch-all term of anthropomorphism, the projection of ourselves onto nature.

Scientists who study animals try to avoid the anthropomorphic error above all else. Even still, I wonder if the cards are simply stacked against eyeless, faceless creatures (or even the “lesser eyed” and “lesser faced”), so that nature’s forms sway our thinking before we can do anything about it. Hume was also correct when he said that reason is the slave of the passions. The eyeless worm on the fishing hook receives little sympathy from me. The quest continues…

I’ll conclude with a passage from Karl Ove Knausgaard, who has written beautifully about eyes, and I’ll continue to wonder from my porch about the ducks and whether they possess the light or not:

“…in the course of life we gaze into thousands of eyes, most of them slipping by unperceived, but then suddenly there is something there, in those very eyes, something you want and which you would do almost anything to be close to. What is it? For it isn’t the pupils you are seeing then, not the irises nor the whites of the eyes. It is the soul, the archaic light of the soul the eyes are filled with, and to gaze into the eyes of the one you love when love is at its most powerful belongs among the highest joys.”

Here’s Quest 21:

See the Eye’s Mind

Key Details:

Support animal cognition research directly. Make a small donation to an organization advancing the study of animal minds. Consider:

The Koko Foundation – For studies in ape language and interspecies communication

The Jane Goodall Institute – Supporting field research in primate behavior

The Animal Welfare Institute – Advocates for humane treatment based on cognitive capacity

Share your favorite photo of an animal. It can be your pet, a creature in the wild, a zoo snapshot, or even a historical or scientific photo that’s stuck with you. What’s your best guess when you look at their eyes? Is anyone home?

Compete in a staring contest with your dog. Only half joking here; our Cavalier Lucy beats me every time. Her mind may be on the smaller side, but she’s determined: I’m pretty sure there’s a there there!

Thanks for reading!