See Less

Shutting your eyes in a culture that never blinks

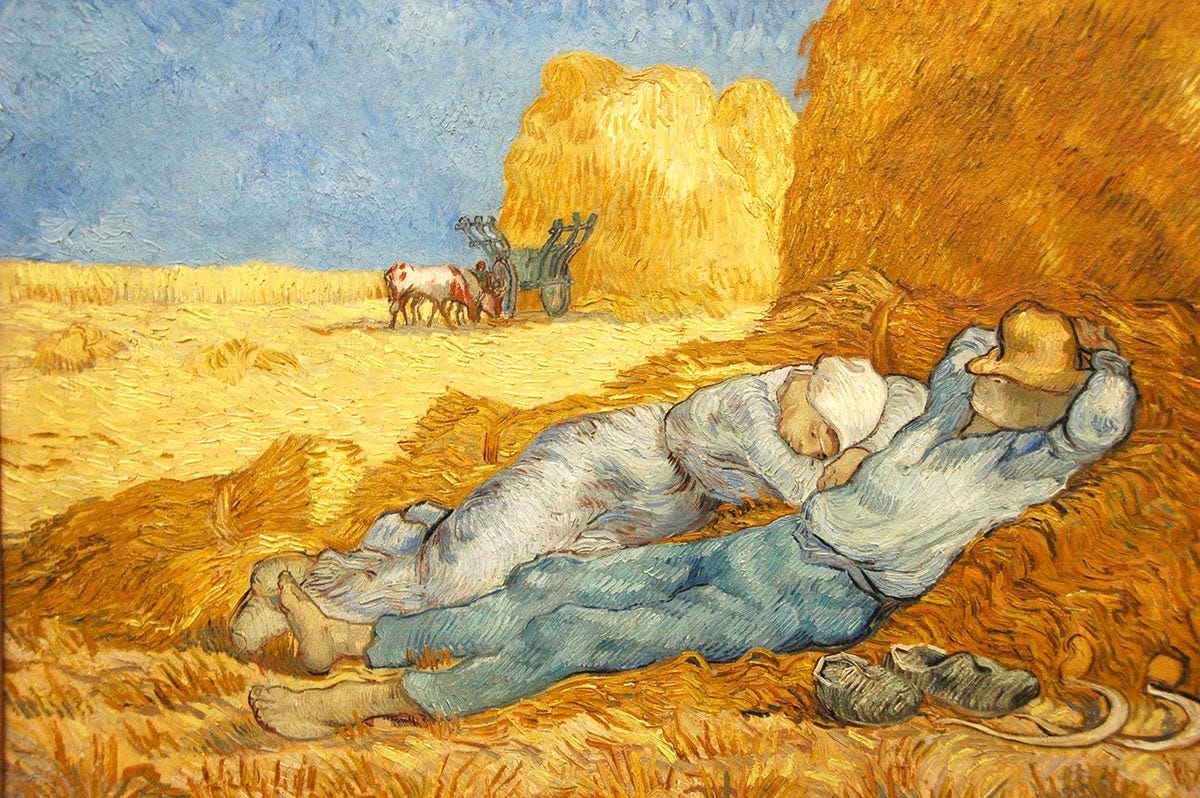

The Siesta, Vincent Van Gogh, 1890

We live in the most visually saturated era in human history. From dawn to dusk, our poor brains are bombarded by images—e-mails and texts; a thousand logos in the grocery store; feeds of people we’ve never met selling products we’ll never buy—and that’s not to mention all the stuff we ostensibly evolved to perceive: you know, like trees and rocks and animals and each other.

You’ve probably seen the little/medium/big screen meme:

“Another day of staring at the big screen while scrolling through my little screen so as to reward myself for staring at the medium screen all week.”

That about sums it up: the world won’t stop showing us things because we can’t stop looking. In 1967, the French philosopher Guy Debord called our civilization of images “the Society of the Spectacle”—if he could only see us now!

It’s difficult to appreciate but there was a time when our visual/semantic systems weren’t permanently overloaded; when segmented sleep was the norm; when close-eyed prayer was commonplace; when the dark was simply dark and people sat in it for hours without freaking out.

Can you imagine how boring that must’ve been?

I’m not here to pretend that we should (or even could) blow up our TVs, throw away our iPhones, and go back to the visual fields of old. We are firmly and irrevocably “in it” now.

And yet it’s obvious that our culture has overwhelmingly privileged sight over sound, touch, taste, and smell; that many of our anxieties stem from our restless hypervigilance, our need to “see for ourselves;” and that we’d probably feel better if we looked a little less and ignored more of what we do see.

Countless pages have been written about how to get off social media, stop doomscrolling, and resist the tyranny of news cycles and the nauseating sense that the sky is falling—(it isn’t).

Perhaps the solution is simple: don’t look! Close your eyes. I mean that literally. Take a nap. At minimum, allow yourself thirty image-less seconds. The world will keep spinning.

Closing your eyes, of course, is a cultural faux pas. To “open your eyes” means to be aware and conscientious. To close them is to look away, to bury your head in the sand, to opt out. Winners maintain eye-contact; losers sleep all day. See the problem?

This week’s quest is an exploration of shut-eyed territory and a call to curate your visual cortex. I’m suggesting seeing less as a means of living better. The advantages touch every part of life—productivity, creativity, athletic performance, and overall well-being. Closing your eyes isn’t a retreat from action but a way to reclaim your sanity.

Benedict Wong as “Marcus” in Weapons—he should probably accept this Quest

(Now, I’m not advocating being a total weirdo. Please don’t shut your eyes at your next dinner party in a guru-esque show of faux-understanding. There’s no new-age enlightenment here. Just a gentle reminder that perhaps we should wean ourselves off the drip-drip-drip of mediated images.)

The benefits of closing your eyes are surprisingly well-documented. If it sounds lazy to you—well, the science disagrees. Let’s dive in.

Power Naps

Humans are not built for unbroken wakefulness.

The idea that we should keep our eyes open for sixteen straight hours—working, yes, but also endlessly entertaining ourselves—is a modern absurdity.

Historically, segmented or “polyphasic” sleep was the norm—first sleep, then a waking interval in the middle of the night, then second sleep. Researchers like A. Roger Ekirch have uncovered thousands of references to “first” and “second sleep” in legal documents, medical texts, and literature. Only with industrialization and artificial light did we compress rest into a single, unbroken stretch.

Research reviewed by Harvard Health make a strong case for a midday nap:

Studies show that naps can enhance mood, reduce fatigue, and improve alertness. Additional research has found that power naps may help decrease blood pressure and improve heart health, especially when taken in the early afternoon. Power naps may support work performance as well. Researchers at NASA found that pilots who napped 20 to 30 minutes were over 50% more alert and over 30% more proficient at their jobs than pilots who didn't nap.

Churchill napped. Edison napped. John F. Kennedy napped. Aristotle, Einstein, DaVinci—all nappers. Salvador Dalí famously perfected the one-second micro-nap: he’d sit in a chair with a key in hand, drift into hypnagogic sleep, and let the key clatter onto a plate, jolting him awake at the threshold of dreaming.

They knew what they were doing. Sleep researchers now argue that opportunistic rest is closer to how the human body is wired. As the UC Berkeley neuroscientist Matthew Walker, author of Why We Sleep, writes: “Humans are not sleeping the way nature intended. The number of sleep bouts, the duration of sleep, and when sleep occurs has all been comprehensively distorted by modernity.”

In short, the nappers aren’t the strange ones. We are.

Prayer and Meditation

For thousands of years, closing one’s eyes was a gesture of reverence, inner peace, and heightened self-awareness. It’s part and parcel of virtually every religion: so ingrained and so obvious that practitioners close their eyes without even questioning why.

Catholics and Protestants alike shut their eyes in prayer; yogis in meditation; Muslims bow five times a day, eyes lowered to the ground.

It ties in neatly to religious metaphysics, going all the way back to Plato. This world is an illusion; there is a deeper reality that our senses—especially vision—tend to obscure. For ancient philosophers and monastic traditions alike, closing the eyes and turning inward was a path to clarity, truth, and calm.

Again, science supports the practice. Sensory deprivation—as in close-eyed prayer or meditation—increases neuroplasticity. There’s also evidence that meditation and prayer increase alpha and theta brain wave activity, which are linked to relaxation and focused attention. The brain, unburdened by constant visual input, retrieves information more efficiently; the mind is freer to wander into stillness.

You don’t have to be religious to learn from practices that’ve worked for humanity across millennia. We’re not concerned here with the truth-claims of these various traditions. The pattern is clear enough: what looks like worship is also a form of rest.

Performance and Productivity

Returning to the secular realm, take note of how often athletes close their eyes. Free-throw shooters shut their eyes, take a breath, open their eyes, bounce-bounce-bounce, and shoot: it’s like an attentional hack connecting them to the basket and their own muscle memory.

Pro golfers, like Jason Day, use visualization techniques before hitting shots. Jack Nicklaus famously called it “going to the movies.” Golf is a game of optical illusions, and closing one’s eyes is a surefire way to ignore visual distractions and rehearse the appropriate physical “feels.”

Jason Day’s pre-shot routine

Studies have shown that close-eyed visualization techniques boost performance nearly as much as actual practice; seeing with the mind’s eye primes the body to respond.

The same principle holds off the court. Closing the eyes reduces cognitive load and improves memory recall. It’s not difficult to see why: constant visual stimuli activate the “Fight or Flight” sympathetic nervous system, whereas eye closure tells our brains and bodies to relax. If there’s no threat to see, then resources can be redirected. Seeing less, paradoxically, helps us process more.

It’s no accident that companies like Google and Cisco have famously experimented with nap pods, “quiet rooms,” and meditation breaks—not out of altruism, but because rested workers think better. Screens fatigue us; so do distractions. The solution is almost comically obvious—just close your damn eyes every once in a while!—and yet we keep looking. For what exactly, it’s hard to say.

Our quest is nearing its end—hopefully you’re getting sleepy. I’ll leave you with one last thought.

There’s a bad idea that’s worked its way into contemporary culture: the notion that you have a moral obligation to pay attention to everything, all the time.

You don’t. In fact, that expectation is probably preventing you from doing real work.

Fundamentally, our obsession with “being informed” is a sequencing mistake. The brain isn’t built for parallel processing on twenty fronts. You’d be better off giving your eyes and your mind a single target—one problem, one email, one piece of art—and then moving on to the next.

In other words: do things in order; ignore everything else.

Jeff Bezos says he spends his mornings “puttering around” before he starts any work. It may sound silly from one of the world’s wealthiest people, but I suspect he’s onto something.

There’s value in doing nothing in particular—in seeing less. When you’re ready, do one thing. And then the next. And then the next.

And with that—

Here’s Quest 29: See Less

Close your eyes for 30 seconds. No one else cares, I promise. You’ll gain a quick appreciation for how image-addicted and “doing”-focused we all truly are.

Nap without guilt. Set a timer and enjoy an afternoon nap. 20 minutes is the sweet spot because while you don’t fall into a deeper sleep and wake up groggy, you still get the benefits of increased alertness and feeling rested.

Look away on purpose. I get it: closing your eyes in public can be weird. As an alternative, just…look away—from a television, a computer screen, anything at all you could use a break from. Curate your visual field.

As always, thanks for reading!