Predict the Future

From Shamans to Algorithms

Giacomo Balla, Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash, 1912. Image.

Welcome back to Quests, where we focus on purpose-driven people and the ideas that animate them.

This week we’ll ascend the Tower, where dreamers, scientists, and technologists construct the world of tomorrow.

We’ll begin on one of its lowest, oldest floors—a space that’s existed as long as humankind has pondered a tantalizing question: What’s going to happen next?

Welcome to the Floor of Prediction.

Here, you’ll encounter shamans, prophets, and oracles, whose ecstatic visions gradually gave way to the analytical forecasts of economists, climatologists, and data scientists wielding powerful models and algorithms. No matter their tools, all seek to glimpse what lies ahead.

This week’s Quest will challenge you to put your own predictive skills to the test in a community contest. May the most clairvoyant adventurer win.

For now, let’s walk the floor and meet the visionaries of past and present.

Prediction Machines

First, a premise: all humans, not just experts, are prediction machines. So argues cognitive scientist Andy Clark in The Experience Machine:

“Contrary to the standard belief that our senses are a kind of passive window onto the world, what is emerging is a picture of an ever-active brain that is always striving to predict what the world might currently have to offer. Those predictions then structure and shape the whole of human experience, from the way we interpret a person’s facial expression, to our feelings of pain, to our plans for an outing to the cinema” (from The Experience Machine, p. xiii).

Prediction, in other words, is not merely something we do when contemplating rain clouds or the stock market; it is the prism through which we experience the world.

Consider Daniel Kahneman’s model of System 1 and System 2 thinking: the fast, automatic judgments we make (System 1) are built on a lifetime of experience—an ability to sense patterns, make snap decisions, and respond in real-time. Meanwhile, the slower, more deliberate thinking of System 2 involves more calculated predictions. We’re always toggling between the two, navigating past, present, and future.

Thinking about prediction can turn into a philosopher’s game: acknowledging that we’re time-bound beings (Heidegger), equipped with mental frameworks to make sense of the world (Kant) who are always balancing memory, perception, and expectation (Augustine). But these are entangling explorations for another day.

For now, let’s focus on the practitioners of prediction, then and now.

Shamans, Prophets, Oracles

In the earliest societies, prediction wasn’t a skill honed through training or technology. It was a mystical power, granted to those with special access to the unseen.

Shamans were the first of these seers. Their power lay in their ability to access what scholars now call Altered State of Consciousness (ASC), and what Mircea Eliade, writing in the 1950s, called “techniques of ecstasy.”

These altered states—induced by trance, ritual, or hallucinogenic substances—allowed them to navigate otherworldly realms, making them mediators between the human and the divine, the present and the future.

The shaman's role in prehistoric societies was central to decision-making, from determining when to plant crops to guiding warriors into battle. Their ability to foresee potential outcomes gave them a unique power over the direction of their community.

(The same holds true of today’s best predictors, who enjoy authority in various arenas: within quant funds identifying winning trades, defense contractors projecting troop movements, political think tanks forecasting electoral outcomes, tech companies capitalizing on consumer behavior, energy companies detecting fluctuations in supply and demand, and on and on. It bears repeating: humans are prediction machines.)

Looking as far back as possible, shamanism, according to historian Martin van Creveld, "far antedates the rise of organized religion, with its hierarchy of priests and followers. No known society, not even one as simple as that of the Andamanese islanders in the Indian Ocean, is without it” ( from Seeing Into The Future: A Short History of Prediction, p. 21).

And yet few traces remain of these earliest diviners. One surviving example is the Bad Dürrenberg Shaman, a 9,000-year-old burial in Germany. Buried with flint tools, animal bones, and ornaments, her grave suggests a shamanic role.

A reconstruction of the Bad Dürrenberg Shaman. Image.

As societies became more structured, so too did the role of prediction.

After the shamans came the prophets ( in the Judeo-Christian-Islamic traditions) and the oracles (in the Ancient Greek and Roman traditions).

Van Creveld writes, “The main difference was that, unlike shamans, they not only lived in literate societies but were often literate themselves” (from Seeing into the Future: A Short History of Prediction, p. 32).

Moses, the archetypal prophet, heard the voice of God in the burning bush, delivered divine law, and foresaw the future of the Israelites. His revelations on Mount Sinai, enshrined in the Ten Commandments, continue to shape our moral sense and political foundations. He embodies the shift from oral to written prophecy.

Moses receives the Ten Commandments. 1860 woodcut. Image.

To simplify:

Prophets & Oracles = Shamans + Writing + Institutionalization

While shamans spoke their personal visions into existence, prophets (from Moses to Mohammad) codified their predictions in sacred texts. Where shamans offered guidance to dozens or hundreds, oracles consulted the rulers of city-states who made sophisticated policy decisions and waged wars impacting hundreds of thousands.

The Oracle of Delphi, or Pythia, portrayed here in a 19th century painting by John Collier, breathes in subterranean vapors to reveal her divine prophecies. Image.

Crucially, the Pythia, high priestess, spoke in cryptic riddles and puzzling ambiguities, not unlike pundits and analysts who hedge their bets with statements like “fair chance” and “distinct possibility.” Vague verbiage in forecasting remains a technique—and a problem—to this day.

It’s easy to dismiss shamans, prophets, and oracles from the vantage point of modernity. We do so only because the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment changed the rules of prediction.

Thinkers like Isaac Newton, Blaise Pascal, and Thomas Bayes took a world steeped in mysticism and gave it the tools of data, probability, and causality.

The Seers of Modernity

With the advent of scientific inquiry, data collection, and mathematical modeling, the nature of prediction changed.

Isaac Newton’s Principia introduced the idea that the future behavior of objects could be predicted based on their current state. Suddenly, prediction wasn’t mystical—it was mechanical.

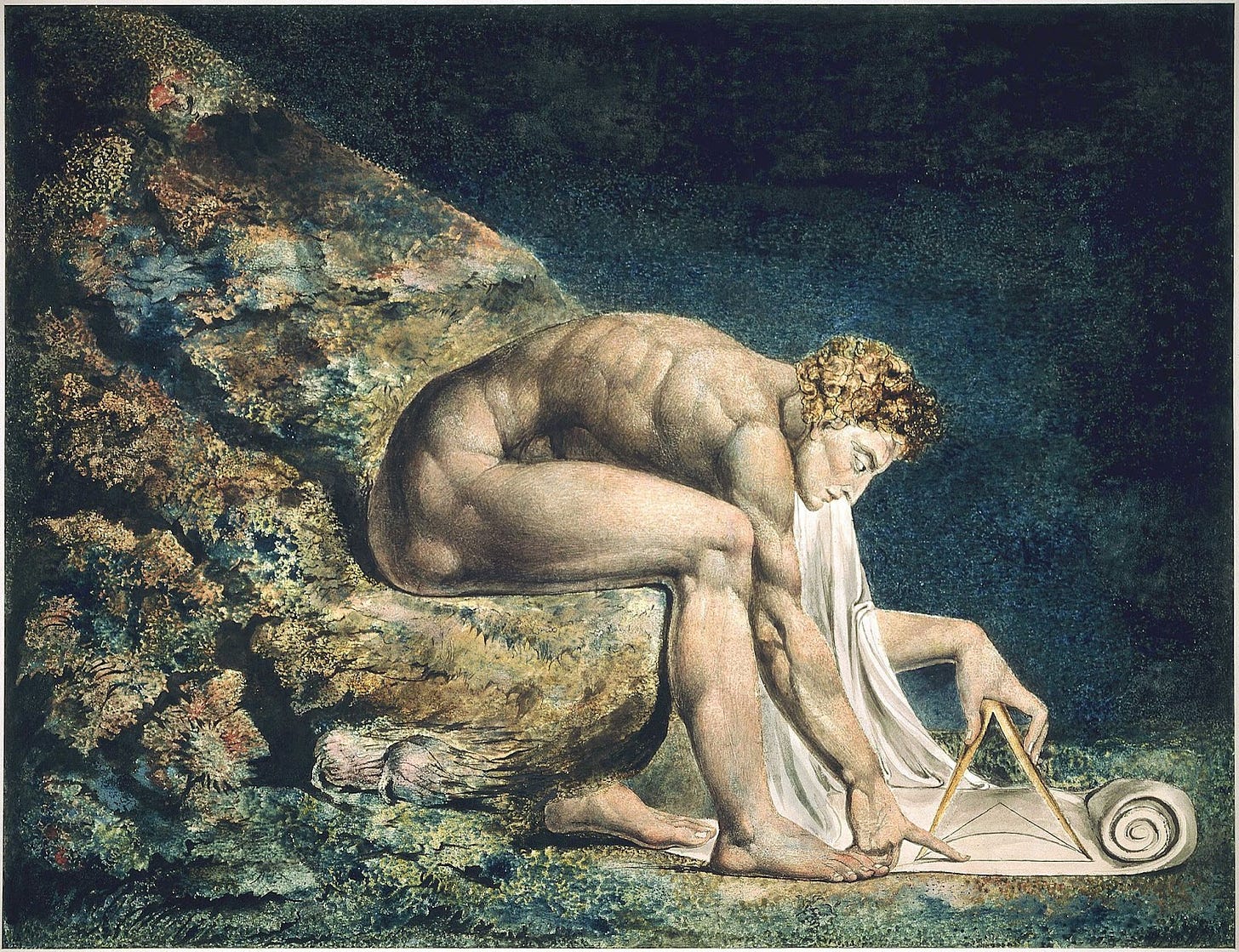

William Blake, Newton, 1805. Image.

“Following the publication of Newton’s Principia mathematica in 1687, which proclaimed a single set of simple laws to cover the movements of all bodies both here on Earth and in the heavens, the popularity of models of this kind soared” (from Seeing into the Future: A Short History of Prediction, p. 207).

Newton imagined a deterministic universe wherein, if you knew all the variables, you could foresee every future event. This set the foundation for probability theory, pioneered by figures like Blaise Pascal, who, in helping a friend solve a gambling puzzle, developed the mathematical frameworks to assess risk and uncertainty.

But even these elegant systems had their limits. Enlightenment thinkers tended to assume that with enough data, everything could be known. But the world is messier than that. These early scientists (or “natural philosophers,” as they were known then) gave us rules but struggled with uncertainty.

Bayesian reasoning filled that gap. Unlike Pascal’s static probabilities, Thomas Bayes introduced something vital: adaptability. Predictions weren’t fixed—they evolved. As new data rolled in, old forecasts had to be updated, revised.

You may have heard the phrase, in the Twittersphere or elsewhere, to “check your priors.” It's a nod to Bayes, namely his idea that your prior beliefs should be updated as new evidence comes in.

In a nutshell, this is Bayes’ Rule: updating beliefs based on new evidence by combining prior knowledge (priors) with new information (data) to calculate probabilities.

Prior probabilities—our initial assumptions about the likelihood of different outcomes—get updated as we gather more data. This is especially useful in situations where we have limited or small amounts of data, such as observing a single coin flip or trying to predict electoral outcomes.

"Bayes’s Rule is dependent on the use of priors... the richer the prior information we bring to Bayes’s Rule, the more useful the predictions we get [...] The best way to make good predictions, as Bayes’s Rule shows us, is to be accurately informed about the things you’re predicting [...] If you want to be a good intuitive Bayesian—if you want to naturally make good predictions, without having to think about what kind of prediction rule is appropriate—you need to protect your priors. Counterintuitively, that might mean turning off the news.

(from Algorithms to Live By, p. 137, 148)

Pair Bayesian thinking with the mighty algorithm—a mathematical set of instructions—and post-World War II computational advances, and you get the modern prediction engine, powered by a constant stream of data.

What’s more, the rise of AI as the next leap in prediction may be one of humanity's most profound achievements. Its impact is already being felt—shaping elections, outperforming markets, and changing the course of wars.

Superforecasters, AI, and You

Prediction has been an especially hot topic over the last two decades or so: during the Obama years, there was a flurry of optimism about forecasting the future.

In 2011, Daniel Kahneman published Thinking, Fast and Slow, and it became a bible of sorts for venture capitalists and decision-makers everywhere. The book revealed the flaws in human judgment and how we can improve our predictions by understanding cognitive biases.

In 2012, Nate Silver released The Signal and the Noise, popularizing Bayesian thinking and shedding light on his process for calling elections with remarkable accuracy. Silver showed how to separate meaningful signals from the noise of misinformation and confusion. His most recent book, On the Edge, pushes too many metaphors too far for my own taste, but his ideas continue to demand attention.

Then in 2015, Phil Tetlock published Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction, which detailed what the world’s best forecasters have in common: humility, adaptability, and the ability to update their views when faced with new data. Influenced by Kahneman, Tetlock showed that superforecasters aren't magical—they’re just more objective and less prone to the biases that affect most of us.

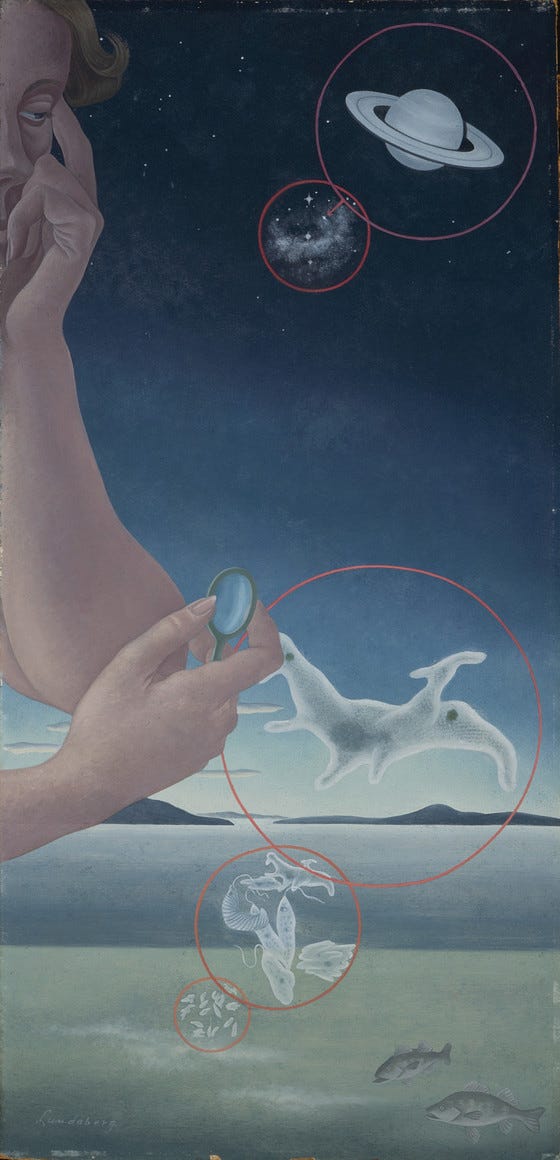

Helen Lunderberg, Microcosm and Macrocosm, 1937. Image.

While academics have been thinking hard about how people make winning predictions, hedge funds, software companies, and defense contractors have turned theory into practice.

Firms like Renaissance Technologies, founded by mathematician Jim Simons, use complex models and high-frequency trading strategies to deliver consistent double-digit returns to their limited partners. Bob Mercer, the former CEO, famously said of the company, “We're right 50.75 percent of the time, but we're 100 percent right 50.75 percent of the time. You can make billions that way.” Check out the Acquired podcast for a deep dive on how Ren Tech has leveraged data predictively at a scale unimaginable just a few decades ago.

Prediction markets like Polymarket and Kalshi are opening new doors for the average person to bet on real-world outcomes. While they democratize forecasting, they also come with risks—critics warn they may encourage frenzied speculation more than informed decision-making. Their success follows the meteoric rise of legalized sportsbooks and gambling platforms. I’ll say it one last time: humans are prediction machines, even when we're wrong!

Then there are software/data analytics companies like Palantir, led by CEO Alex Karp, whose name references Tolkien’s all-seeing stones in Lord of the Rings. Palantir integrates vast stores of data to help clients, especially the U.S. government, make more accurate predictions. Allegedly, their software played a role in finding Osama bin Laden, and today, Palantir’s technology is being used to forecast everything from cyberattacks to global supply chain disruptions.

Meanwhile, defense contractors like Lockheed Martin are integrating predictive AI into military technology, with the F-35 serving as a prime example. This advanced fighter jet leverages machine learning to sharpen pilot situational awareness. The company’s Collaborative Combat Aircraft program goes even further, envisioning autonomous drones working in tandem with manned jets. It isn’t much of a leap to imagine the sci-fi doom scenario of flying killer robots: unmanned systems that can predict enemy movements and target them with ease.

This is the darker side of prediction. Regulation and oversight will be critical in the coming decades. In today’s cultural environment, where shared values are more contested than ever, balancing progress with ethics will require informed citizens willing to take action.

That’s where you come in, adventurer.

Let’s exit the Tower—it can be a dizzying place!—and focus on how you can apply these ideas to your own life and take predictive action.

First, you don’t need a crystal ball. But you do need a mindset. Drawing from the insights of Phil Tetlock, Nate Silver, and other top experts, here are some key principles to help you improve your forecasting skills:

Denarrativization: Humans love stories, but they often cloud our judgment. Focus on facts and probabilities rather than narratives. Look past media hype (ignore the daily news, read periodicals/magazines/books instead) and stick to the data.

The Importance of Doubt: Doubt isn’t a weakness; it’s a tool. The best predictors constantly question their assumptions. Stay open to being wrong.

Probabilistic Forecasting: Don’t think in absolutes. Assign probabilities to outcomes and adjust as new data comes in.

The Wisdom of Crowds: Collective intelligence often outperforms individual judgment. Pay attention to expert consensus and aggregated data. Prediction markets, indexes, and funds of funds thrive on this principle—so should you.

High-Quality Data: Not all data is equal. Prioritize reliable, up-to-date information. Bad data leads to bad predictions.

Real-Time Response: Don’t be static. Great forecasters constantly revise based on new information. Prediction is a process—stay agile and adjust as the playing field evolves.

Now, it’s your turn. Put these principles into practice, and join this week’s Quest.

Here’s Quest 2:

Predict the end-of-day value of the S & P 500 on December 31, 2024.

Key Details

The value of the S & P 500 as of today’s posting (10/10/24 at ~11AM) is 5,779.

Predictions due by 11/30/2024.

Predictions made in October get a 10% accuracy bonus (i.e., if your prediction is within 50 points of the actual S&P 500 closing price on 12/31/24, your score will be adjusted as if it was within 45 points).

Make your case in the comments or at the Quests Community. Or email me directly at joshwilbur@gmail.com. Try using some of the ideas discussed here—(maybe not the shamanic use of hallucinogenic substances) — and share your bull or bear case.

The winner will receive a write-up in a future post, an exclusive badge, and, most important of all, bragging rights among Quests readers.

Hopefully unnecessary disclaimer: This is a community contest for fun, not financial or investment advice.

Please comment here on Substack with thoughts, counterthoughts, suggestions, and disagreements.

To tumble further down the rabbit hole, head over to the Quests Community.

Upon completion:

It’s dangerous to go alone—find a quest partner, and party up.

Recommended Reading:

The Signal and the Noise by Nate Silver

Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction by Phil Tetlock

Algorithms to Live By by Brian Christian and Tom Griffiths

Seeing into the Future: A Short History of Prediction by Martin van Creveld

How Data Happened by Chris Wiggins and Matthew L. Jones

Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy by Mircea Eliade

The Experience Machine by Andy Clark

NEXT ON QUESTS

Next week, we'll head back to the Town Square to take on the issue of voter turnout in America. Why isn’t everyone registered to vote? Which party actually benefits when more people register? The answers might not be what you expect, and the quest will be nothing short of epic. Be ready for a deep dive into the politics of participation—and how you can play a role.

In the meantime, quest on.