Fund Teachers

Support the professionals who know best

The education non-profit space is treacherous.

As watchdogs like Charity Navigator frequently highlight, too many organizations are drowning in overhead.

They burn cash on elaborate galas, administrative salaries, and teams of staff whose prime directive is to justify their existence to checked-out boards of directors.

Intentions are vague; execution is often lacking. Countless ed-orgs claim to “spearhead change,” seek “innovative solutions,” or “advocate” for students. But look beyond all this linguistic massaging, and there’s not much to see: a few grants, a glossy annual report, a pilot program that never scaled.

They do some good, yes, but they could do better.

Every extra layer of management is a tax on your donation. By the time your dollar finally reaches its destination, it’s been whittled down significantly.

I look for organizations that funnel money as directly and clearly as possible—and with receipts. There should be no doubt about where the money is going or how it’s getting there.

The shorter the elevator pitch, the better.

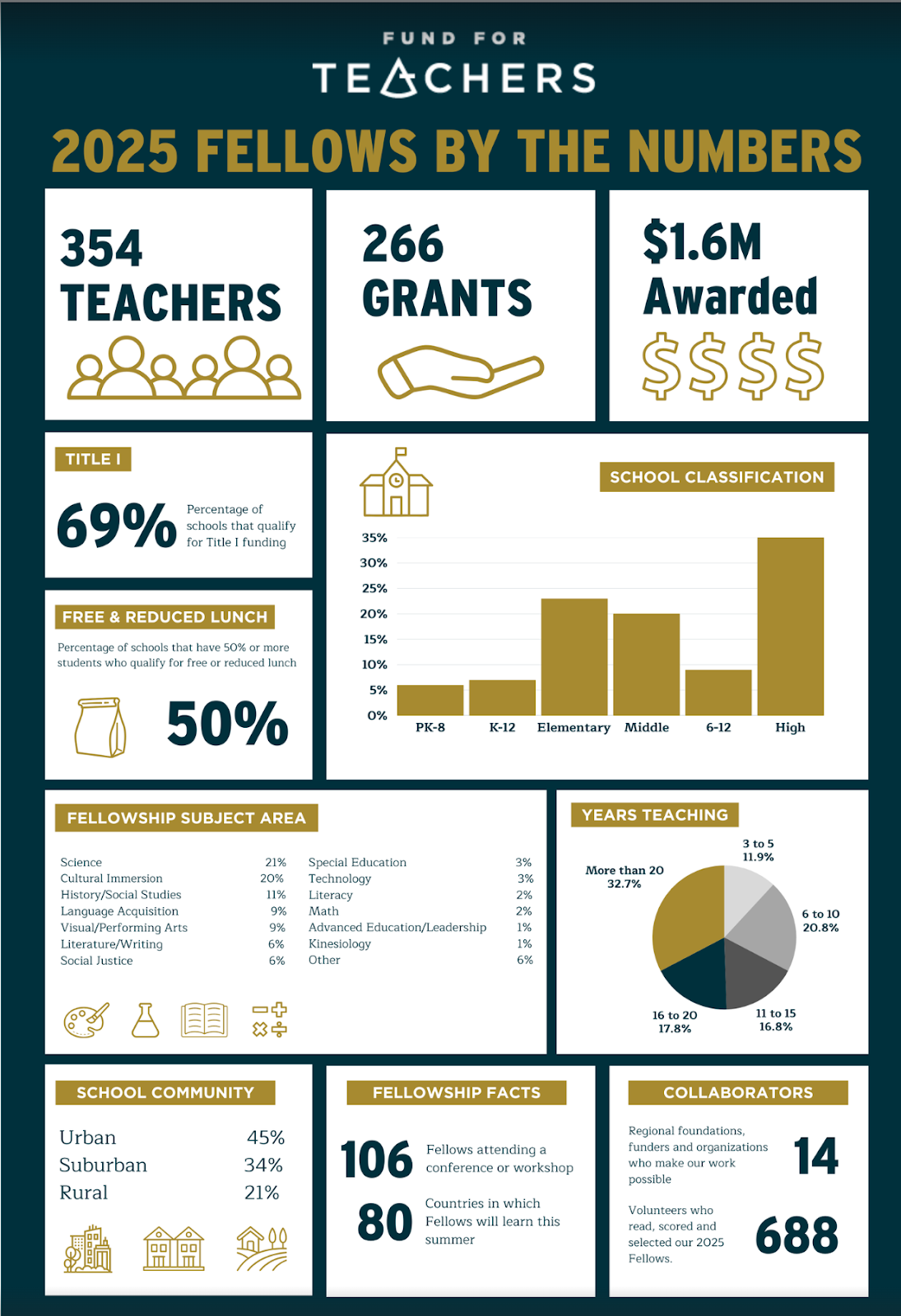

Fund for Teachers’ pitch is about as short as it gets. They give money to teachers.

For more than 20 years, FFT has operated on a simple premise: Teachers are the experts. They know their own gaps. They know their students’ specific deficits. If you give them the capital and the agency to design their own professional development, they will optimize it better than any central planner could.

The Professional Development Trap

I remember as a kid when teachers were out for workshop days. My first thought was “Hell yeah!”—or whatever the nine-year old version of that sentiment is—since it usually meant watching a movie on one of these bad boys:

My second thought was: what’s a “workshop?” What is Professional Development (PD) for educators?

It sounds great in theory: train teachers to be better. In reality, PD is an “an enormous sinkhole, sucking billions of dollars every year and producing no measurable results,” according to TNTP. Teachers drudge their way through banal “sessions” and stale luncheons. And for what?

Every year, U.S. school systems collectively spend thousands of dollars per teacher on PD, with some large districts reaching or exceeding $18,000 per teacher once salaries, coaching, and vendor contracts are fully loaded. In some school systems, this can consume close to 10% of the school year in training days, meetings, and mandated sessions.

What’s the return on that sizable investment?

Multiple studies have found that the dominant workshop-style PD model produces little to no measurable, sustained improvement in most teachers’ classroom performance.

To put it more bluntly, as one thread on r/Teachers does: “Professional Development is the biggest waste of time that any human being could ever experience.”

That’s probably harsh, but the core problem is well-established: the people choosing the training (district administrators looking for a silver bullet) are not the people doing the job (teachers on the ground). What you end up with are one-size-fits-all seminars that have little to do with the specific history, algebra, or reading curriculum a teacher is struggling to deliver to a room of 30 distinct human beings. There’s little inspiration; no stories to bring back to the students; just a ho-hum going through the motions: everything wrong with the education system in a nutshell.

Enter Fund for Teachers.

Fund for Teachers

Fund for Teachers (FFT) flips the model, treating teachers like the professionals they are—akin to a doctor or lawyer who identifies a deficit in their practice and seeks out specific training to fix it.

It effectively creates a localized market solution. The teacher identifies the demand (a gap in student knowledge), proposes the supply (like a fellowship or research trip), and FFT provides the capital. For their efficiency and transparency, Fund for Teachers boasts a 96% rating from Charity Navigator.

The organization’s core philosophy is refreshingly simple: “We have trusted teachers to design their own professional learning because teachers can and should be charged with knowing their students deeply.”

FFT Fellows

When you unbundle professional development from the usual bureaucracy, it looks a lot different.

Consider the following examples from the FFT 2025 Fellow class:

An English teacher who works with students on the autism spectrum. She identified a disconnect in how her students engaged with traditional texts, so she attended a “Shakespeare and Autism” program at Ohio State University, learning how to use theater games to help neurodivergent kids.

Two teachers from a rural school who traveled to Fishlake National Forest in Utah. They went to study Pando—a massive colony of quaking aspen that is technically the largest living organism on earth—so they could build a science curriculum that gets students out of the textbook and into the outdoors.

A teacher whose district lacks any curriculum for gifted and talented students. She traveled to a global conference in Portugal to learn how to incorporate artificial intelligence and social-emotional support into her curriculum.

Rural STEM teachers who traveled to Japan to study sustainable fishing practices. They brought that global data back to students in farming communities who are facing their own resource management crises.

You can see more examples from the 2025 fellow class here. In each case, the idea is to treat teachers like principal investigators rather than assembly line workers. After all, they know best what their students need. It’s a great example of injecting cash into a common sense solution.

Viewed through a wider lens, this philanthropic approach mirrors a structural shift in American generosity—a move toward charity that deliberately bypasses the top-down architectures of the twentieth century.

If the old guard of giving was defined by the institutional weight of a Rockefeller or a Ford Foundation—gatekeepers of best practices and centralized strategy—the current moment increasingly favors the logic of orgs like GiveDirectly and Fund for Teachers, operating on the premise that individuals know best how to solve their own challenges.

It’s a bet on the idea that the most efficient way to improve education is to simply trust and empower the person standing at the front of the room.

For these reasons, I’m excited for Quests to donate $110 to Fund for Teachers ($55 subscriber dollars: $670 in annual revenue ÷ 12 months + my own matching $55 donation)

Also, it felt serendipitous that this past week the New York Times ran a story highlighting education non-profits to support. Here’s what they said:

“ [...] both major parties have allowed education to move to the back burner of American politics, and student achievement has declined in recent years.

For Americans who want to help fill the void, we have a suggestion. This holiday season, The New York Times Communities Fund has partnered with seven evidence-based charities that invest in education at critical junctures across people’s life spans. We urge readers to consider donating.”

If you’re more excited about any of those orgs, consider making a holiday donation; this is a big time of year for non-profits as they try to hit their budget goals.

And thanks for reading the Education questline! Next time I’ll look to add another wrinkle to the Quests formula, with a new thematic focus and a new organization to support at the end of our adventure. Stay tuned!

Love this!