Fail Fast

Embracing imperfection in the age of AI

Stenographic Figure, Jackson Pollock, 1942

I once wrote an email to a fancy executive whose business we, i.e., my employer at the time, wanted badly.

I fretted over the message and spent an hour considering every word, every bullet point. Eventually, I asked an older, grizzled colleague to look it over.

“Good email, but too clean. Throw in some incomplete sentences.”

Excuse me?

“It’s more authentic that way. And you don’t want it to seem like you care quite so much.”

He was absolutely right. There was something overly earnest and too buttoned-up about my original email. It was the sort of text that AI can now produce in seconds: cloying and sycophantic but also dry as a bone. Lifeless.

I needed to write something imperfect, something human. Oddly enough, that’s arguably harder now with so many powerful tools at our disposal. It’s too tempting to plug words and images into an LLM, to over-craft everything.

While perfection is a great goal for a machine, it’s absolutely stultifying for a human being. We need to be free to make mistakes, and lots of them.

Today’s quest is part pep-talk, part user-friendly guide, explaining why you should fail a lot—in art, business, sports, your personal life—and how to screw up more efficiently. We’ll meet some folks along the way who’ve failed wonderfully in their own quests, making beautiful mistakes (thanks Maroon 5) and happy accidents (thanks Bob Ross) for the rest of us to enjoy.

Better AI Means Fewer Mistakes — Why That’s Bad

The phrase “AI slop” gets thrown around a lot these days. It’s become something of a misnomer. AI-generated text, code, images, and video are actually getting really good! That’s probably not news to you.

What may be surprising is that perfection, not slop, is a problem in itself.

For now, AI outputs are like Ikea furniture: cold, functional, modular—perfect in their way—but lacking that element of spark or personality.

Nearly a hundred years ago, the German philosopher Walter Benjamin called the magical quality of an artwork its “aura.” He argued that the “age of mechanical reproduction,” with its photography, film, and mass production, had stripped art of its aura.

The situation’s only worsened (improved? worse-proved?) with LLMs. College students churn out perfectly functional Chat GPT-written essays: “Everyone Is Cheating Their Way Through College,” reads a recent NYMag headline. A large chunk of the comments I see on Reddit and X/Twitter now are written by or alongside a chatbot—and they’re often pretty good! Real estate listings, customer service chats, pitch decks, political campaign emails, Amazon reviews, LinkedIn posts—everything has the same polish, the same cadence, the same uncanny lack of human fingerprints.

It’s all perfectly clean, but it reveals a lack of taste, an absence of personality. It’s clear, but it’s not especially cool. There’s no aura to it.

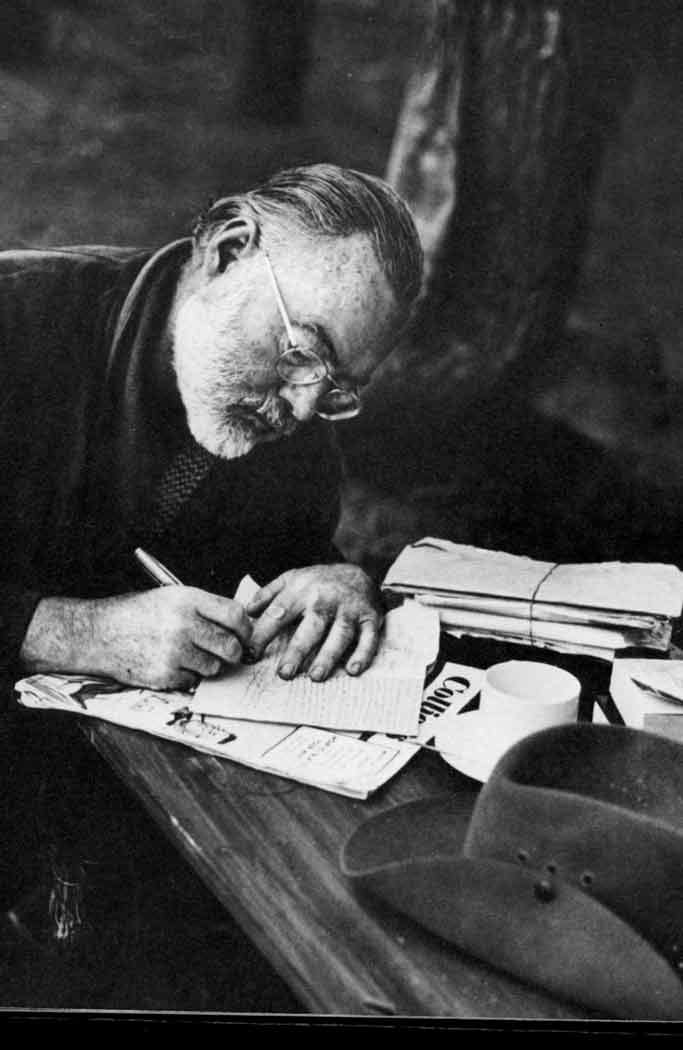

Artistic flair and creative progress—in writing, business, sports, anything—require errors along the way, the visible breadcrumbs of a human consciousness needling its way through a problem. Ernest Hemingway rewriting The Sun Also Rises, omitting large portions of rejected drafts. Steve Jobs and his team of engineers reworking the original Macintosh over and over again. Serena Williams improving her forehand after breaking her wrist riding a skateboard.

Ernest Hemingway embodied the old Elmore Leonard quote: “If it sounds like writing, I rewrite it.”

That’s the most interesting thing to other people: that a human being struggled and stumbled their way into something—there’s no better word for it—beautiful.

When that struggle is absent, other people can feel it. It’s aura-less. They won’t want your art and won’t buy your product. It’s really that simple.

What’s more, without mistakes, there’s little room for discovery, iteration, and the unknown.

LLMs are making the benefits of failure harder to appreciate. Why write/code/design anything when a machine can do it better, faster, stronger?

Well, because the flaws are precisely the point…

Action is Information

I have rewritten—often several times—every word I have ever published. My pencils outlast their erasers.

—Vladimir Nabokov, Russian-American novelist

“I've missed more than 9000 shots in my career. I've lost almost 300 games. 26 times I've been trusted to take the game winning shot and missed. I've failed over and over and over again in my life. And that is why I succeed.”

—Michael Jordan in a classic Nike ad

“Action is information”

—Brian Armstrong, CEO of Coinbase

If you listen to some of the most successful investors, founders, entrepreneurs—builders of all stripes—you’ll hear a common refrain: fail fast.

They all repeat this same cliché in various guises—Move fast and break things. You can just do things. Iterate. Pivot. These are intelligent people who are wary of clichés and often pride themselves in being different. And yet on this topic they sound like talking parrots: fail, fail, fail!

They endorse failure, again and again, for two reasons: (1) it’s the best advice out there and (2) it’s extremely difficult to follow.

Artists give exactly the same advice, and they can shed additional light on why failure feels so bad.

Steven Pressfield, in one of the best books on creativity ever written, The War of Art, calls it Resistance. This psychological force—Pressfield is almost Freudian in his description—frustrates our creative ambitions. It’s the fear of failure dressed up as perfectionism. It’s the artist’s oldest foe. Failure stirs something in us from childhood, from our school days, from mean teachers and stern figures; “We’re all recovering children,” according to the famous psychoanalytic saying.

Pressfield’s advice is to show up anyway. To understand that this failure-adverse force, this fear of failure, exists in the hearts and souls of everyone—it’s always going to be a thing—and to just get your butt in the chair. Create something, even if (especially if!) it’s messy. It’s a muscle that will strengthen over time.

Some of my favorite works of art are the sort of painstaking masterpieces that—in their very strangeness—reveal the countless mistakes that must have been made to create them: Lawrence of Arabia (part war film, part character study, an unwieldy 4 hour odyssey filmed in the desert and starring the flawed, magnificent Peter O’Toole); The Downward Spiral (Trent Reznor’s industrial rock magnum opus, layering hundreds of tracks and leaving in countless mic pops and audio glitches); Ulysses (James Joyce’s’ modernist novel, reimaging a single day in a sprawl of experimentation that took him seven years to complete).

Peter O’Toole in Lawrence of Arabia

Athletes, like artists, live in a world where failure isn’t just possible but inevitable, total, and spectacularly public. It’s why we watch: the possibility of failure is the drama.

And after all: some of the greatest plays in sports are world-class athletes making mistakes and then gloriously recovering from them. Michael Jordan’s stumbling fadeaways; Tiger Woods’ impossible chip-ins; Lionel Messi’s rapid-fire steps, missteps, recoveries, goals.

Failure for athletes is data. Each missed shot, each lost match, each botched start is a lesson carved into muscle memory. We’d do well to imitate them: to act, to generate information, to be what Teddy Roosevelt called “the man who is actually in the arena.”

Cliché right?

Maybe, but: ignore this particular truism at your own peril. Failing fast, no matter how many times you might need to hear it, is the key to success. So let’s get to failing—together.

Okay, you get the point! Failure is valuable, and you should try to make more mistakes in your daily life—not haphazardly, but with an eye for artistic magic (aura) and interpersonal connection.

Here’s Quest 22:

Fail Fast

Key Details

I’ve touched on how technology can impede our ability to make productive mistakes…but it can also help. What’s key is your order of operations: fail first, and then use Chat-GPT. Prioritize outreach: use an AI agent to reach out to ten people, instead of one or two. Use “vibe-coding” tools like Replit, Cursor, or Windsurf to create a working prototype; then build the real thing. Every iteration helps.

Whether you use technology or not; here’s a simple objective toward completing this quest: Make the crudest prototype (i.e., completable in twenty minutes or less) of whatever thing you have in your head. Set a timer and write something. Send an email—right now. Film a short video; record a piece of music; share the results with friends, family, coworkers, and your fellow adventurers here at Quests.

Share an example in the comments below of your greatest creative/professional mistakes, and what came from them: hopefully the positive upshot, but anything goes!

Thanks for reading, and good luck in all your misadventures!

Fail quickly and fail cheaply is a mantra in the video game business. Thank you Phil Harrison.

Rapid iteration on every aspect of the product, including business plans. Is critical for success.

The real challenge is having the financial runway to iterate as long as it takes.