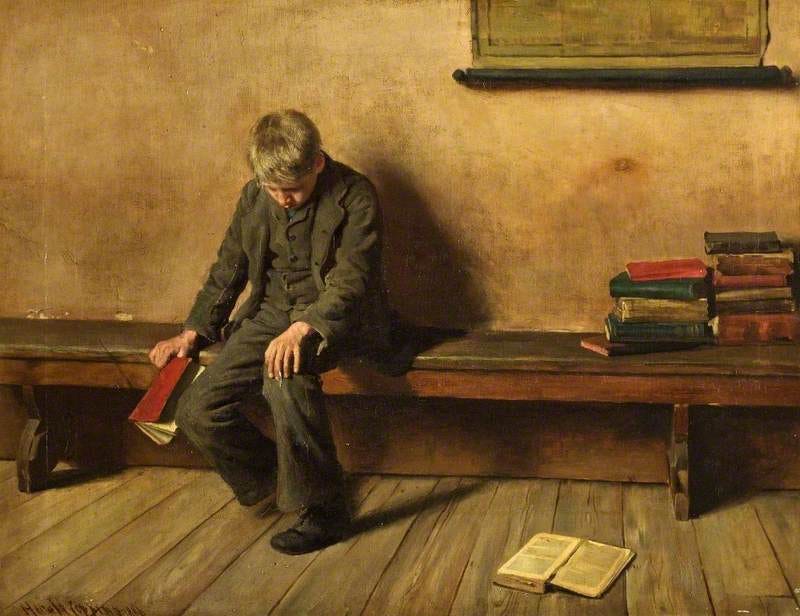

The Dunce, Harold Copping, 1886

Greetings, adventurer. Big journeys lie ahead here at Quests—colonizing Mars, exploring the ocean’s depths, investigating the new science of sleep. I’m excited to bring in some experts to touch on some of these topics, and join our ragtag party of curious minds.

But before we set off, let’s linger in the Town Square for just a moment.

By the steps of the courthouse, a group jeers at a speaker, heckling her every word. Near the tavern, a scholar waves a parchment, scoffing at the simpletons who don’t grasp her argument. A merchant mutters under his breath, shaking his head at the “fools” who don’t understand basic economics.

Are we really surrounded by idiots? Or is something broken in our discourse?

No doubt, something’s changed in recent years: a creeping assumption has taken root, a quiet certainty that other people aren’t just wrong — they’re dumb.

It’s not hard to see why.

Trust in major societal institutions has crumbled. Surveys indicate that confidence in entities like the federal government, news media, and higher education has reached historically low levels. A 2023 Gallup poll reported that only 36% of Americans have "a great deal" or "quite a lot" of confidence in higher education, down from 57% in 2015.

A global assessment revealed that American adults, particularly those with lower education levels, struggle with basic tasks such as making inferences from texts and performing simple mathematical operations. The percentage of U.S. adults with math skills not surpassing primary-school levels increased to 34% from 29% in 2017.

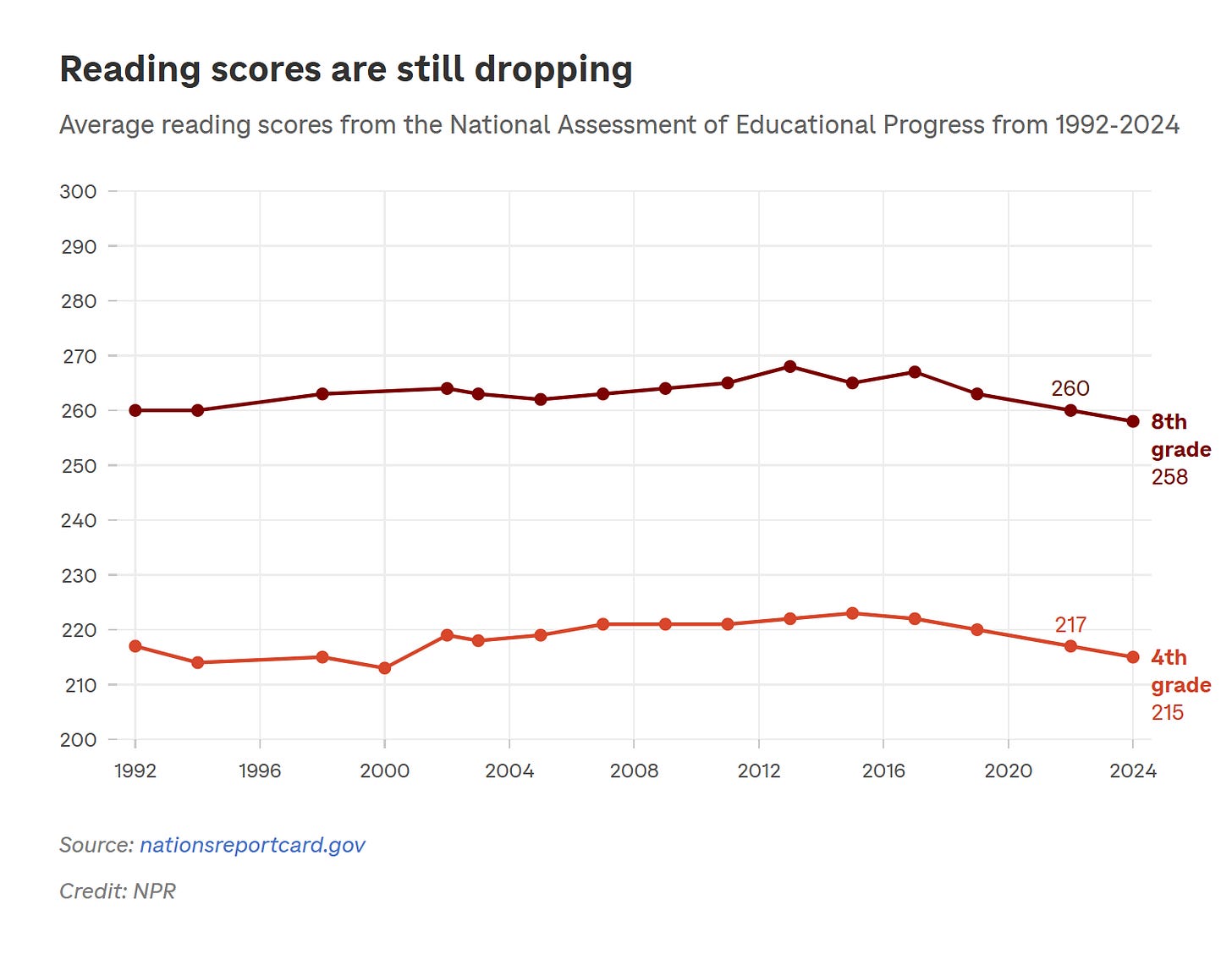

And then there’s the deepening crisis in literacy and reading skills, recently underlined in a new report from the National Assessment of Educational Progress. Children are reading less, reading worse, and retaining almost nothing. Adults aren’t faring much better, according to a report from the American Enterprise Institute.

Inarguably, our education system, media landscape, and political processes are a broken mess.

And yes, there’s a fascinating debate to be had about intelligence today. Is it measurable? Is it declining? Are we, as a species, getting dumber as our lives become defined by easy conveniences and the outsourcing of difficult work?

Perhaps.

But I’m not interested in these questions at the moment. I want to focus on our thoughts and our language. Does anyone actually benefit from mental models that assume the inanity of others?

I’m reminded of the old George Carlin joke: “Think of how stupid the average person is, and realize half of them are stupider than that.”

A sharp joke from a great comic. But this kind of cynicism corrodes everything. Let’s look at the anatomy of our insults and understand what’s happening sociologically.

In-Groups and Out-Groups

Donald Trump is not an idiot.

He is many things—including the worst offender of name-calling in American political history—but he is not an idiot.

Nor is Elon Musk. Or Joe Biden. Or Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. Or whoever else dominates the national conversation on a given week.

And yet Reddit and Twitter threads, Facebook comments, and news headlines are littered with people dismissing their opponents as “stupid.” Donald Trump called Nancy Pelosi “really stupid” at a 2019 rally. In 2021, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi called House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy a “moron” for his views on mask mandates. And in her recent 2024 book, the former House Speaker Pelosi wrote of Donald Trump: “I’ve had a lot of conversations with this man, and at the end of nearly all of them, I think, ‘Either you are stupid, or you think that the rest of us are’.”

How many “idiots” do you see?

That about sums it up. And that’s just five minutes of Googling around one politician. Stupid discourse is everywhere.

In one sense, it’s shorthand— a cognitive shortcut, a way to quickly signal our allegiances and place ourselves within tribes. This is classic in-group vs. out-group psychology, a phenomenon studied by social psychologists like Henri Tajfel and Muzafer Sherif.

Tajfel’s Social Identity Theory explains how people derive self-esteem from group membership, leading them to exaggerate differences between their in-group (the “rational,” “intelligent” people) and the out-group (the “stupid,” “irrational” ones). This is why political discourse so often devolves into name-calling—calling someone “stupid” reinforces a sense of belonging among those who already agree.

Sherif’s Robbers Cave Experiment demonstrated how quickly arbitrary group divisions can escalate into hostility, even when there’s no fundamental difference between the groups. In his study, two groups of boys at a summer camp, initially unaware of each other, quickly became rivals the moment they were put into competition. The parallels to our media and political landscapes are obvious: the more we define “the other” as dumb, the more we strengthen our own group identity.

It’s tribalism in the digital age. It reminds me of another old joke, this one from Jerry Seinfeld: we don’t cheer for people; we cheer for clothes. The instinct to divide—to root for our team and jeer at the other side—has always been around: the Ancient Greeks lobbed their share of insults, for example. The impulse is simply amplified now, fueled by algorithms that reward outrage.

That said, in-grouping doesn’t provide a full explanation for our kneejerk, “what an idiot”-isms. I encounter stupid people all the time, even when I’m alone and signaling no allegiances to no-body.

What then?

Ice and Egos

I was driving the other day after the big winter storm that hit the East Coast. Here in Charleston, South Carolina, we don’t usually see much snow or ice. So I shouldn’t have been surprised by the woman in the white SUV; I saw her, but she didn’t see me.

I know she didn’t see me because with the exception of a small porthole perhaps the size of a grapefruit, her windshield remained completely covered in a thick sheet of ice. She drove, blindly, at ten miles per hour, slamming her brakes periodically and swerving from lane to lane.

This, I thought to myself, had to be the dumbest person alive.

Let’s unpack this a bit. I’ve lived in cold-weather climates, so I knew to run my car for a few minutes before pulling out of the driveway. I knew not to brake aggressively on icy roads. And I knew to clear the entire windshield of ice, not just a face-sized sliver as if I was Tom Hanks in Apollo 13.

Apollo 13, a film about intelligent astronauts

It’s safe to assume that this person had zero experience driving in icy weather. She was probably panicked, perhaps running late for work, maybe physically unable to clear the whole windshield. I have no idea. But, more likely than not, she’s a perfectly capable person in other walks of life; she acted foolishly, but she’s no fool.

I think at the heart of this brief, icy exchange is (1) a mismatch in experience and (2) egoism at work. On the first point, we tend to judge others most harshly in the areas where we feel most competent. This is the mechanic who scoffs at the idiot who doesn’t know to check his oil; the DMV worker who rolls his eyes at the woman who didn’t first fill out Form 400; the financier who can’t believe anyone would carry credit card debit. If you pay attention, you’ll catch yourself doing this all time; it’s a perfectly natural bad habit.

Ego plays a role here as well. It’s the part of the psyche that mediates between our raw impulses (the id) and the rules of reality (the superego). It’s the voice inside all of us—that voice was a child once, remember?—that says, “You belong, you’re doing a good job, keep it up.” This internalized egoic voice likes to be fed, and the stupidity of others makes for delicious, satiating food.

I know what to do to make the teacher proud. None of the other kids do, ha!

I actually think Nancy Pelosi was correct when she said that Donald Trump thinks everyone else is stupid. That is exactly what he thinks. And that doesn’t make him an idiot; it makes him a man with an ego of the wildest and strangest proportions, a psychoanalytic case study like no other. And that’s far more dangerous.

Toward A Less Stupid Discourse

Are people ignorant?

Yes.

Are people misinformed, under informed, or blinded by bias?

Yes.

Are people self-serving, greedy, prejudiced?

Yes, yes, and yes.

But, by and large, they are not stupid in the proper sense of the word. It is woefully imprecise to say so, and it lets them off the hook for their actions.

My conclusion here is that stupidity, idiocy—whatever you want to call it—isn’t a particularly useful concept. It’s lazy. It flattens complexity. It’s an excuse to avoid engagement.

We can and should do better.

The people in the Town Square look a little different now.

The shouting has softened, the lines between “us” and “them” a little less rigid. Maybe not everyone is an idiot after all—maybe some are just wrong (which is different from stupid!), or misinformed, or seeing something from an angle we haven’t considered.

So as we look ahead to future adventures, let’s avoid the stupidity trap.

Here’s Quest 11:

Escape stupidity

Key Details

Alright, this quest might seem a little touchy-feely, but it doesn’t have to be moralizing or prescriptive. I’m simply suggesting you change up your patterns of assumption and share some examples of interacting differently.

Challenge yourself to read a book, article, or essay written by someone whose perspective you usually write off. Try to understand, not just refute. If you’re conservative, read Harper’s Magazine; if you’re liberal, read the National Review. Be gracious.

Highlight the intelligence of someone you disagree with.

Or diagnose the flaws in their argument—but do so respectfully and item by item, without name calling. You’ll notice that it’s more difficult and time-consuming. And, yes, humanizing.

Complete this quest, log it @ the Quests Community, and you’ll earn the Town Square badge on your adventurer profile.

And, as always, thanks for reading!

I really dug this post. I was just looking at a very conservative new-release book earlier and my knee-jerk reaction was to dismiss it entirely as zealous nonsense, but a small part of me said it might be insightful to read it and understand.